Research Article

Volume 4 Issue 4 - 2022

Determinants of Agro-pastoral households’ diversification of income in Hamer District, South OMO Zone, Southern Ethiopia

1Southern Agricultural Research Institute, Jinka Agricultural Research Center, Agricultural Economics and Gender Researchers, SNNPR, Jinka, Ethiopia

2Goal Ethiopia, Non-governmental Organization, Livestock expert, SNNPR, Jinka, Ethiopia

2Goal Ethiopia, Non-governmental Organization, Livestock expert, SNNPR, Jinka, Ethiopia

*Corresponding Author: Asmera Adicha, Southern Agricultural Research Institute, Jinka Agricultural Research Center, Agricultural Economics and Gender Researchers, SNNPR, Jinka, Ethiopia.

Received: October 08, 2022; Published: November 03, 2022

Abstract

This paper examines the determinants of the diversification of income and its share of total household income among agro-pastoral households using a cross-sectional survey design data collected from Hamer District, Southern Ethiopia. The study employed multistage and purposive sampling techniques in the selection of 156 agro pastorals. The data were collected through a structured interview. Descriptive statistics were used to explore the correlation between the diversification of income and demographic, institutional, and socio-economic factors whereas the Censored Tobit model was used to identify determinants of agro-pastoral household's income diversification. The result revealed that farm income sources were the most important income source for agro-pastorals in the sampled site contributing 86.02% of total household income with the remaining 13.98% originating from non-farm and off-farm income sources. The most important motive for income diversification is to avoid livestock selling, availability of external support, and the existence of recurrent drought. The levels of income diversification were affected positively by sex of respondent, draught power/oxen number, farm size, extension contact, and membership in opportunities and negatively affected by market distance. The result shows the contribution of farm income sources to the entire income of respondents is high and income diversification is not well practiced in the area. Therefore, government and stakeholders should continue their efforts in forming non-farm and off-farm business cooperatives to generate income-earning opportunities in the rural areas and support the agro-pastoralists to enhance non-farm and off-farm business activities productivity through supportive policies including input provision, creating a market for their product and accessing roads.

Keywords: Determinants; Income Diversification; Censored Tobit Regression; Agro pastoral

Introduction

Agricultural productions are mainly based in farming and pastoral areas and are the economic backbone of most developing countries including Ethiopia. Depending on a country's level of advancement in the economic sphere, it contributes to overall economic growth by creating jobs, supplying labor, food, and raw materials to other growing sectors of the economy; and helping to generate foreign exchange (Zerihun, 2012). In Ethiopia, farming strategies emphasize agricultural development mainly on-farm and do not focus on good chances for non-farm livelihood diversification activities. Nevertheless, in Ethiopia, a decline of insufficiency of food and its fundamental extermination in all its extents have remained and quiet is the overruling improvement plan of the country. Although almost all of the people have been working in consumable item production and are unable to feed a comparatively huge proportion of the people from its national production that about 83% are involved in agricultural production and the rest 27% are involved in non-agricultural economic activities (MoFED, 2006; MoARD, 2007 and WB, 2009). Individual household or national policies that protect rural incomes must take into account how important it is for households to diversify their sources of income (Minot et al., 2006). About 60% of the entire labor force are involved in various works all intended at mitigating the special effects of economic and agro-climatic tremors, food shortage reduction, consumption steadiness, and whole development in the living standard of the households in fewer industrialized nations (Soares, 2005).

Livelihood diversification in pastoral and agro-pastoral are mainly based on livestock-related diversification including fodder production, value-added activities related to livestock rearing and marketing (e.g. milk processing and sale), and agro-pastoralism. Alternative livelihoods like investment in new, especially urban-based medium and low wage income, income from collection and sale of natural resources (e.g. charcoal, firewood, mining), agriculture, trading (e.g. food or cloths), remittances from relatives in urban centers or aboard (IFAD, 2018). The experiences of the past two decades showed that pastoralism as one means of existence is becoming difficult due to internal and external multidimensional factors and pastoralists are searching for other livelihood portfolios through a diversification process (Dinku, 2018).

The livelihood of pastoral and agro-pastorals in Malle District of the South Omo zone does not only depend on the rearing of livestock and crop production, but it also relies on different survival activities like off-farm or non-farm that substitute the accumulation of additional capital and coping strategy for the attainment of self-sufficiency and reducing poverty (Algaga and Sisay, 2020).

In the earlier empirical literature, various studies examined factors affecting the diversification of income in rural parts of Ethiopia. Nevertheless, studies on factors of agro pastoral household diversification of income are limited in pastoralist and agro-pastoral areas of the South Omo zone. Particularly in Hamer District, it is not well known whether there exists variability in the diversification of income among agro pastorals in the study sites. Besides, some agro-pastoral in the area (sample site) allocate their working time between farms and non-farm activities to have a secure income for their family members while others engaged in farming only. It is not clear why some households engage only in farm activities while others engage in both farm and non-farm income-generating activities. Involvement in non-agricultural activities offers supplementary income that allows farmers to expend more on their rudimentary requirements including food, education, closing, and health care. This implies that non-farm employment has a significant role in maintaining household nutrition safety (Zerai and Gebreegziabher, 2011; Oyewole and Henson, 2012; Yizengaw, 2014). Policy makers and others did not look at how rural income diversification is integrated with employment generation and other food security status improvement strategies due to a lack of empirical evidence that helps understand well. Therefore, this study was designed to identify determinants of agro-pastoral household’s diversification of income in Hamer District, South Omo zone; Sothern Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

The Study Site Description

Hamer District is one among the eight administrative Districts of the South Omo zone, Southern Ethiopia in which this study was done. It is located between 40?45?? to 50? 18?? N and 36? 014?? to 36? 041?? in the Southern part of the South Omo zone at 766, 541, and 100 km from Addis Ababa, Regional and zonal towns respectively. According to Hamer District's main administration office's unpublished data of 2015, the total population of the District was estimated at 75,056, Out of these 71,489 are rural dwellers 'and the remaining 3,567 are residing in urban. Of the population in the District, women constitute 49.2% and men 50.8%. Male and Female household heads were estimated at 14292 (10719 male HH and 3573 female HH). Of the total 35 kebeles in the District, 24 are agro-pastorals, and 11 are pastorals. The highest and lowest altitude of the District ranges is between 2084 and371masl. Its agro-ecology is kola and climatic conditions are characterized by 8% dry woina dega, 37.5% semi-arid, 54.45% arid, and 0.05% desert. The lowest and highest environmental temperature ranges between 29-38 degrees Celsius. The total area of the Hamer District is estimated at 731,565ha, of which 8,865 ha is cultivated on rain-fed agriculture. The vast land which covers 250,939 and 225,434 is bush and shrub and grazing land respectively. The remaining 137,067 ha is occupied by settlements and wasteland (SOFEDD, 2009). Livestock is the main source of income and food source and is culturally considered as prestige in the community. In the Hamer District, there were about 717362 cattle, 1,172,037 goats, and 525833 sheep. The District has the largest share of the livestock population in the South Omo zone 19.05% of cattle, 35.9% of goats, and 29.88% of sheep (Asmera et al., 2021). Beekeeping was also the usual practice of the majority of Hamer communities.

Hamer District is one among the eight administrative Districts of the South Omo zone, Southern Ethiopia in which this study was done. It is located between 40?45?? to 50? 18?? N and 36? 014?? to 36? 041?? in the Southern part of the South Omo zone at 766, 541, and 100 km from Addis Ababa, Regional and zonal towns respectively. According to Hamer District's main administration office's unpublished data of 2015, the total population of the District was estimated at 75,056, Out of these 71,489 are rural dwellers 'and the remaining 3,567 are residing in urban. Of the population in the District, women constitute 49.2% and men 50.8%. Male and Female household heads were estimated at 14292 (10719 male HH and 3573 female HH). Of the total 35 kebeles in the District, 24 are agro-pastorals, and 11 are pastorals. The highest and lowest altitude of the District ranges is between 2084 and371masl. Its agro-ecology is kola and climatic conditions are characterized by 8% dry woina dega, 37.5% semi-arid, 54.45% arid, and 0.05% desert. The lowest and highest environmental temperature ranges between 29-38 degrees Celsius. The total area of the Hamer District is estimated at 731,565ha, of which 8,865 ha is cultivated on rain-fed agriculture. The vast land which covers 250,939 and 225,434 is bush and shrub and grazing land respectively. The remaining 137,067 ha is occupied by settlements and wasteland (SOFEDD, 2009). Livestock is the main source of income and food source and is culturally considered as prestige in the community. In the Hamer District, there were about 717362 cattle, 1,172,037 goats, and 525833 sheep. The District has the largest share of the livestock population in the South Omo zone 19.05% of cattle, 35.9% of goats, and 29.88% of sheep (Asmera et al., 2021). Beekeeping was also the usual practice of the majority of Hamer communities.

Sorghum and Maize are the main food crops produced in rain-fed and flood recede farming systems. The District receives rain in two seasons. The long season of rain (Belg rain) which is expected after half of February and ended in the second week of May is vital for crop production in agro-pastoral kebeles and pasture regeneration in pastoral and agro-pastoral kebeles of the District. The short season rain which uses as a bridge for the long dry season livestock pasture and water sources rains between mid-September to the last October or from mid of October to mid of November, despite its fall has become fluctuating as belg rain season (SOFEDD, 2009).

Research Design

Cross-sectional survey design data was collected in the logic that relevant data was collected at some point in time. A descriptive survey (household survey approach) was employed for this study. The survey approach was selected because it has the advantage of providing information on large groups of people with little effort and in a cost-effective manner.

Cross-sectional survey design data was collected in the logic that relevant data was collected at some point in time. A descriptive survey (household survey approach) was employed for this study. The survey approach was selected because it has the advantage of providing information on large groups of people with little effort and in a cost-effective manner.

Sampling Techniques and Sample Size Determination

In this study, multistage and purposive sampling techniques were followed to select the sample District, kebeles, and sample households. The Hamer District was first recognized because it includes agro pastoralists in income-diverse activities. In the second stage, discussing with the Hamer District agricultural office sample kebeles were identified and of those five kebele were randomly selected. Lastly, sample respondents were randomly selected from each selected kebeles based on probability proportional to the size of their sample size producer distribution.

In this study, multistage and purposive sampling techniques were followed to select the sample District, kebeles, and sample households. The Hamer District was first recognized because it includes agro pastoralists in income-diverse activities. In the second stage, discussing with the Hamer District agricultural office sample kebeles were identified and of those five kebele were randomly selected. Lastly, sample respondents were randomly selected from each selected kebeles based on probability proportional to the size of their sample size producer distribution.

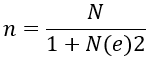

The fundamental elements to take into account when choosing the right sample size are the users desired level of precision, the confidence level desired, and the degree of variability. Thus, it will be determined using a simplified formula provided by (Yemane, 1967).

Where: n = sample size N = household size and e = level of precision, the formula is valid for a 95% confidence level and p=0.5 (the level of variability assumed to exist in the population which is the maximum level in this case).

Data Types and Sources of Data

We used both primary and secondary data sources. Primary data were collected from smallholder agro-pastoralists and kebele experts in the study District. The secondary data are relevant to the study as supplementary information to strengthen the primary information provided by the sample household heads for the rational conclusion. The sources of the secondary data were the zonal and District Agricultural Office. Furthermore, a list of different and relevant published and unpublished reports and bulletins from the Central Statistical Agency were used as secondary data.

We used both primary and secondary data sources. Primary data were collected from smallholder agro-pastoralists and kebele experts in the study District. The secondary data are relevant to the study as supplementary information to strengthen the primary information provided by the sample household heads for the rational conclusion. The sources of the secondary data were the zonal and District Agricultural Office. Furthermore, a list of different and relevant published and unpublished reports and bulletins from the Central Statistical Agency were used as secondary data.

Tools Used for Data Collection

Tools used for data collection were key informant interviews with zonal, District, and kebele experts, three focus group discussions with model agro pastorals, pastorals elders, youth, women, and development agents on sample kebeles, and final (156 respondents) household survey using interview schedules through structured questionnaires. In addition documents from District government sector offices like the livestock and fisheries department, the Agricultural and natural resource department, and other relevant sources were studied to support the main data and to get detailed information.

Tools used for data collection were key informant interviews with zonal, District, and kebele experts, three focus group discussions with model agro pastorals, pastorals elders, youth, women, and development agents on sample kebeles, and final (156 respondents) household survey using interview schedules through structured questionnaires. In addition documents from District government sector offices like the livestock and fisheries department, the Agricultural and natural resource department, and other relevant sources were studied to support the main data and to get detailed information.

Data Analysis Methods

The collected data were analyzed by using both descriptive and Censored Tobit models. The quantitative were computed using SPSS version 23 and STATA 14 to clarify the main results and socioeconomic situations.

The Result of the Descriptive Analysis

The collected data were subjected to simple descriptive statistics like mean, maximum, minimum, frequency, percentage, and standard deviation, and used to explain demographic, institutional, and socio-economic features of households to reflect the respondent’s diversification of income.

The collected data were subjected to simple descriptive statistics like mean, maximum, minimum, frequency, percentage, and standard deviation, and used to explain demographic, institutional, and socio-economic features of households to reflect the respondent’s diversification of income.

Econometric A pproach

The censored Tobit Regression Model was used to analyze factors affecting the diversification of income in agro-pastoral households.

Simpson Index of Diversity (SID)

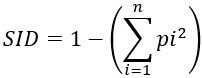

The diversification index was measured with the help of the Simpson index of diversity. The

Simpson's index of diversity is defined as:

The censored Tobit Regression Model was used to analyze factors affecting the diversification of income in agro-pastoral households.

Simpson Index of Diversity (SID)

The diversification index was measured with the help of the Simpson index of diversity. The

Simpson's index of diversity is defined as:

Here, SID= Simpson’s Index of Diversity

N= the total number of income source

Pi= income proportion of the ith income source

SID's value is always between 0 and 1. Pi=1 and SID=0 if there is only one source of income. The shares (Pi) and the total of the squared shares decrease as the number of sources rises, bringing SID closer to 1. The greatest SID will belong to households with the most diverse earnings, and the smallest SID will belong to those with the least diverse incomes. SID assumes its minimal value of zero for the least diversified households (those dependent on a single source of income). The number of available income sources and their relative shares determine the SID upper limit, which is one. The value of SID increases with both the number of income sources and the distribution of income shares. As it balances, the Simpson Index of Diversity is influenced by both the number of revenue sources and the distribution of income among them (Minot et al., 2006; Joshi et al., 2003). The SID approaches 1 as revenue from each source is more evenly distributed.

N= the total number of income source

Pi= income proportion of the ith income source

SID's value is always between 0 and 1. Pi=1 and SID=0 if there is only one source of income. The shares (Pi) and the total of the squared shares decrease as the number of sources rises, bringing SID closer to 1. The greatest SID will belong to households with the most diverse earnings, and the smallest SID will belong to those with the least diverse incomes. SID assumes its minimal value of zero for the least diversified households (those dependent on a single source of income). The number of available income sources and their relative shares determine the SID upper limit, which is one. The value of SID increases with both the number of income sources and the distribution of income shares. As it balances, the Simpson Index of Diversity is influenced by both the number of revenue sources and the distribution of income among them (Minot et al., 2006; Joshi et al., 2003). The SID approaches 1 as revenue from each source is more evenly distributed.

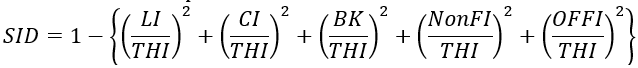

In this study, the SID model is expressed as:

Where LI = Livestock income, CI = Crop income, BK = Beekeeping income, Non FI = non-farm income, OFFI = off-farm income sources, and THI = Total household income from all income sources.

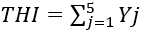

The sum of Total Household Income (THI) is given as:

Where: THI=Total Household Income, thus income coming from all sources j. j=1, 2, 3, 4….5, farm and Non-farm income.

Censored Tobit Regression

The agro pastoralists' income diversification using the censored Tobit regression model was the study's aim variable. Analysis of the variables influencing the diversification of income in agro-pastoral households was done using the censored Tobit regression model. Using the Simpson diversity index, the level of diversification was divided into two groups for this analysis: 1) Non-diversified households are those with very few other sources of income, and the majority of their income comes from the sale of livestock and livestock products. 2) Diversified households are those with additional sources of income such as crop production, honey beekeeping, non-farm, off-farm work, and other sources. A household was considered to have a diverse livelihood for this study if it engaged in numerous income-generating economic activities in addition to agro-pastoralism. Using Simpson's Index of Diversity, the degree of diversification was assessed in terms of both the number of income sources and the balance of income coming from various sources (SID). The general formulation for Tobit specification is given (Greene, 2003) as:

The agro pastoralists' income diversification using the censored Tobit regression model was the study's aim variable. Analysis of the variables influencing the diversification of income in agro-pastoral households was done using the censored Tobit regression model. Using the Simpson diversity index, the level of diversification was divided into two groups for this analysis: 1) Non-diversified households are those with very few other sources of income, and the majority of their income comes from the sale of livestock and livestock products. 2) Diversified households are those with additional sources of income such as crop production, honey beekeeping, non-farm, off-farm work, and other sources. A household was considered to have a diverse livelihood for this study if it engaged in numerous income-generating economic activities in addition to agro-pastoralism. Using Simpson's Index of Diversity, the degree of diversification was assessed in terms of both the number of income sources and the balance of income coming from various sources (SID). The general formulation for Tobit specification is given (Greene, 2003) as:

Where yi* is a censored variable of the Simpson diversity Index (SID), β is a parameter to be estimated, x is a vector of explanatory variables and ? is the error term. Determining diversification of income (SID);

SID= β0+ β1age+ β2 sex+ β3edu+ β4adult equivalent + β5farmsize + β6TLU +β7cooperative +β8market distance +β9 oxen no +β10extcontact +β11 access to information+β12acccredit +? ... (6)

SID = is the Simpsons Index of Diversity, ε = error term

Description of Variables and Working Hypothesis

Dependent variable: The dependent variable is Simpson Index Diversity (SID). The value of SID always ranges between 0 and 1. If there is just one source of income, Pi=1, so SID=0. As the number of sources increases, the shares (Pi) decline, as does the sum of the squared shares, so that SID approaches 1. Accordingly, households with the utmost diversified incomes will have the biggest SID, and the fewer diversified incomes are related to the lowest SID.

Dependent variable: The dependent variable is Simpson Index Diversity (SID). The value of SID always ranges between 0 and 1. If there is just one source of income, Pi=1, so SID=0. As the number of sources increases, the shares (Pi) decline, as does the sum of the squared shares, so that SID approaches 1. Accordingly, households with the utmost diversified incomes will have the biggest SID, and the fewer diversified incomes are related to the lowest SID.

Independent variables: Table 2 illustrates the variable description, measurement of variables, and prior expectations. Several institutional, demographic, and socio-economic variables are predicted to influence the diversification of income in the study site. The main independent variables assumed to influence agro-pastoral households' diversification of income positively or negatively are described below.

| Variables | Measurement | Expected sign |

| Dependent variables | ||

| diversification of income (SID) | An index value of SID (1 if HHds diversify, 0 otherwise) | |

| Explanatory variables | ||

| Sex | 1 if male agro-pastoralists, 0 if female agro-pastoralists | + |

| Age | Years | + |

| Education | Years of schooling (0=illiterate, 1= otherwise) | + |

| Adult Equivalent | Total of household size in a household living for more than 6 months (adult equivalent) | + |

| Farm size | The mean land held by a household(ha) | + |

| TLU | Number of livestock owned in (TLU) | + |

| Extension contact | Number of contact with extension agents in a month | + |

| Use of Credit | 1 if access to and get credit, 0 otherwise | + |

| Cooperatives membership | 1 if participate in cooperative, 0 otherwise | + |

| Distance to the market center | Distance to nearest market center (minute) | - |

| Number of oxen | Number of oxen/drought power (number) | + |

| Access to information | if access to and get information, 0 otherwise | + |

Source: own description after intensive literature review

Table 1: Explanatory variables defined in the Censored Tobit Regression.

Table 1: Explanatory variables defined in the Censored Tobit Regression.

Results and Discussions

Descriptive Statistics Analysis Result

Demographic and socio-economic features of agro-pastoral households

This section presents descriptive statistics of demographic and socio-economic features of respondents because they influence income diversification in agro-pastoral households. Additionally, District Agricultural and Natural Resource Management, Livestock and Fishery Resource Office, and kebele experts were asked to provide information regarding the income diversification of agro-pastoral households to meet the specific objectives. Thus, demographic and socio-economic features of the study site are presented and described in table 3 and table 4 with continuous and categorical variables.

Demographic and socio-economic features of agro-pastoral households

This section presents descriptive statistics of demographic and socio-economic features of respondents because they influence income diversification in agro-pastoral households. Additionally, District Agricultural and Natural Resource Management, Livestock and Fishery Resource Office, and kebele experts were asked to provide information regarding the income diversification of agro-pastoral households to meet the specific objectives. Thus, demographic and socio-economic features of the study site are presented and described in table 3 and table 4 with continuous and categorical variables.

The results described in Table 3 represent the descriptive statistics of continuous variables with income diversification. The minimum and maximum ages of respondents were 19 and 68 years respectively with a standard deviation of 8.89. The mean age of the agro-pastoral was 36.12 years, suggesting that the respondents were in their active age group. Besides, the correlation between the age of the respondent and the Simpson diversification index is insignificant. The average adult equivalent of the respondents was 5.52. The spreading of the sample household by household size (adult equivalent) was a minimum of 1.1 and a maximum of 10.4 with a standard deviation of 2.53. The influence of household size (adult equivalent) in on-farm supports that, the accessibility of labor for on-farm activities mainly keeping livestock, bee keeping, and other off-farm activities are determined by the amount of the household size. Additionally, the correlation between household size (adult equivalent) and the Simpson diversification index is insignificant.

The minimum and maximum farm size of respondents was 0.5 and 2.125 hectares respectively with a standard deviation of 0.51 hectares. The average land of the respondents was 1.41 hectares. This implies that households have relatively good average landholding and they have a chance to diversify household income like crops and livestock to improve their livelihood activities. Also, the correlation between farm size of the household and SID is significant and positive at a 1% probability level.

Extension contact is provided by development agents and to some extent by non-governmental organizations. One to two development agents were assigned at each Kebele to give frequent and continuous technical support and advice. Almost all sample households of the survey had responded that development agents have been assigned and they visit a minimum of 1 time, a maximum of 5 times, and on average 3 times in a month with a standard deviation of 1.59. But most of them complained that they do not get sufficient agricultural extension services like a technological problems, technical support, and follow-up on income diversifying activities as they are pastoral and agro-pastoral. Likewise, extension contact of the household and SID correlate significantly and positively at a 1% probability level.

Distance from the market was considered one factor affecting the diversification of income. The minimum and maximum distance required to arrive at the nearest market center were 1 kilometer (10 minutes) and 19 kilometers (190 minutes) respectively. The average distance by sample households is about 1.27 kilometers (12 minutes) with a standard deviation of 0.93 kilometers (9 minutes). The correlation between market distance and the Simpson diversification index is insignificant.

The result indicated that the respondents own 26.16 TLU on average with a standard deviation of 21.19 TLU. The maximum and the minimum tropical livestock unit were 189.2 and 0.3 TLU respectively. The livestock unit of the household and SID does not correlate.

The mean number of oxen for respondents in the area was found to be 6.03. The household had a minimum and maximum numbers of oxen were 2 and 18 respectively with a standard deviation of 2.74. As they are pastoral or agro-pastoral there are a large number of oxen in the area. Furthermore, the numbers of oxen the household had and SID correlate significantly and positively at a 1% probability level.

| Diversification index (SID) | |||||

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Correlation Coeff. (p-value) |

| Age | 36.1218 | 8.889 | 19 | 68 | -0.0254 (p = 0.7525) |

| No oxen | 6.0320 | 2.7437 | 2 | 18 | 0.2089 (p = 0.0089) |

| Market distance | 1.2707 | 0.9302 | 1 | 3.7 | -0.0653 (p = 0.4179) |

| Extension contacts | 3.1410 | 1.5921 | 1 | 5 | 0.2331(p = 0.0034) |

| TLU | 26.1565 | 21.1942 | 0.3 | 189.2 | 0.0717(p = 0.3738) |

| Farm size | 1.4122 | 0.5149 | 0.5 | 2.125 | 0.2851(p = 0.0003) |

| Adult equivalent | 5.5288 | 2.5333 | 1.1 | 10.4 | -0.0084(p = 0.9174) |

Source: Survey result, 2021

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of continuous variables with income diversification.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of continuous variables with income diversification.

Table 4 describes the descriptive statistics of categorical variables with income diversification. Of the total sample households, 69.2% were male and the remaining 30.8 were female-headed households. The result of the P-value indicated that there is a statistically significant correlation between the sex of households and the diversification of income at a 1% probability level.

Concerning the agricultural cooperative membership of the respondents, only 25.6% of the sample households were a member of agricultural cooperatives, and most of them (74.4%) do not take part in agricultural cooperatives membership. The presence of an agricultural cooperative member facilitates and makes it easy to get agricultural inputs, drugs, and credit services. Indeed a small number of respondents benefited from being a member of agricultural cooperatives. The P-value result indicates that there is no significant correlation between the involvement of agricultural cooperatives and the non-involvement of agricultural cooperatives in the household’s diversification of income index.

Access to and utilization of credit has a positive result to raise agricultural productivity. About 64.7 % of the respondents haven’t gotten credit services and haven’t utilized whereas 35.3 % of the sample household had credit access, this suggests that the additional access to credit the enhanced diversification of income. The P-value result indicates that there is no significant correlation between having access to credit services and having no access to credit services on the household's diversification of income index.

From key informant interviews and focus group discussions, it is well-known that income diversification is indomitable by the availability of diverse wealth resources such as monetary provision like credit access and capacity building, infrastructures, and facilities such as extension support and practical training for households’ on-farm and off-farm activities. This assists every household to have additional elasticity in undertaking income diversification to improve their livelihood.

Access to information about the market, and agricultural technology contribute to on-farm and non-farm production activities. This is because households having access to market information and recent agricultural technologies can increase farm production and productivity. On the study site, about 34% of respondents have access to market and agricultural technologies whereas 66% have no information about market and agricultural technologies. Indeed, agro-pastoralists are not getting recent market and agricultural technology information on the study site. The P-value result demonstrates that there is no significant correlation between having access to agricultural information and having no access to agricultural information on the household’s diversification of income index.

Concerning education, respondents indicated about 94.23% of respondents were illiterate and only 5.77% were literate, and most of them were illiterate. Education achievement is very vital since it might clue to a consciousness of the potential benefits of up-to-date agricultural skills and enhance the expansion of respondent’s incomes. The P-value result confirms that there is no significant correlation between literate and illiterate households on the level of the income diversification index.

| Variables | Diversification index (SID) | |||

| Freq | % | Correlation Coeff.(p-value) | ||

| Sex | Male | 108 | 69.2 | 0.2340 (p = 0.0033) |

| Female | 48 | 30.8 | ||

| Membership in cooperatives | Yes | 40 | 25.6 | -0.0133 (p = 0.8694) |

| No | 116 | 74.4 | ||

| Access to credit | Yes | 55 | 35.3 | -0.0711(p = 0.3778) |

| No | 101 | 64.7 | ||

| Access to information | Yes | 53 | 34 | -0.0797 (p = 0.3227) |

| No | 103 | 66 | ||

| Education level | 1 | 9 | 5.8 | 0.0603 (p = 0.4548) |

| 0 | 147 | 94.2 | ||

Source: Survey result, 2021

Table 3: Descriptive statistics of categorical variables with income diversification.

Table 3: Descriptive statistics of categorical variables with income diversification.

Share of different income sources to agro-pastoral households

Agro-pastoral households’ income sources

Different scholars classify income sources of rural households differently by considering the situation of that particular study site. The study by Mohammed and Fentahun (2020) classified income sources in Asayita District as farm income, formal wage employment, non-formal wage employment, self-employment, remittance, and rental income. Other scholars classified income sources as farm income, non-farm income, off-farm income, remittance, and others. Batoo et al. (2017); Agyeman et al. (2014) classified income sources as farm and non-farm in their study site. Given reviewing different works of literature and giving due consideration to the study site, this study followed Ellis's (2000) classification of household income. These are farm income, off-farm, and non-farm income. Farm income sources in this study are income from crop production, livestock and its product, and honey beekeeping. Off-farm income in the study sites was income from the sale of charcoal, fuel wood, gum, and incense. Non-farm income sources in the study sites were income aid from the government and different NGOs, making local drinks, and livestock trading. Agro pastoral households in the study site are initiated to diversify their income activities, although their livelihood mainly depends on husbandry which involves dominant livestock and supportive crop production, or both. Non-agriculture and off-farm activities have remained to support rural households.

Agro-pastoral households’ income sources

Different scholars classify income sources of rural households differently by considering the situation of that particular study site. The study by Mohammed and Fentahun (2020) classified income sources in Asayita District as farm income, formal wage employment, non-formal wage employment, self-employment, remittance, and rental income. Other scholars classified income sources as farm income, non-farm income, off-farm income, remittance, and others. Batoo et al. (2017); Agyeman et al. (2014) classified income sources as farm and non-farm in their study site. Given reviewing different works of literature and giving due consideration to the study site, this study followed Ellis's (2000) classification of household income. These are farm income, off-farm, and non-farm income. Farm income sources in this study are income from crop production, livestock and its product, and honey beekeeping. Off-farm income in the study sites was income from the sale of charcoal, fuel wood, gum, and incense. Non-farm income sources in the study sites were income aid from the government and different NGOs, making local drinks, and livestock trading. Agro pastoral households in the study site are initiated to diversify their income activities, although their livelihood mainly depends on husbandry which involves dominant livestock and supportive crop production, or both. Non-agriculture and off-farm activities have remained to support rural households.

As shown in table 6 different income bases were identified which give to the whole family income. The mean total income of respondents is 44021 Ethiopian Birr produced from a wide-ranging income-generating base. The farm income sources account for 86.02 % of households who diversify their income into livestock (65.86%), crop (12.19%) and beekeeping (7.97%) while non-farm and off-farm activities contribute 13.68% and 0.3% of the total income respectively. This suggests that the further the agro pastorals diversified their on-farm income, the greater the contribution of on-farm income activities to the total household income. This is highly consistent with the works of (Ibekwe et al., 2010; Muhdin, 2015; Amanze, 2011; and Yisihake and Abebe, 2016). But, this finding is highly inconsistent with the works of Croppenstedt (2006) and Awoniyi and Salman (2011). Additionally, on average the annual portion of the income from non-farm and off-farm activities represents 6024.74 (13.68%) and 128 (0.3%) of total household income respectively. This share fits reasonably into the available recent literature from other countries (Ibekwe et al., 2010, Deininger and Olinto, 2001; Woldenhanna and Oskam, 2001). This low non-farm and off-farm income confirm the less share of income from non-farm and off-farm activities which may aggravate the level of poverty among the rural households and poses aid from the government and NGOs.

As per focus group discussion with experts, model agro pastorals, and elders, they indicated that non-farm and off-farm income seals the difference between production from survival agriculture and damage from climate variability. Known for the determining tendency of decreasing farm income production in the study sites, the acquiring of additional sources of income is fetching a necessity.

The key informant argument with District and kebele experts reflected that respondents in the study sites are involved in non-farm income tasks such as the trade of oxen, goats, and sheep, and sale of the local drink, and other off-farm income sources such as charcoal sale, gum, and incense selling. They distinguished that, contrasting on-farm activities; income from non-farm and off-farm income prospects is not simply ruined by tremors like extensive drought and climate variability. Besides, respondents involved in non-farm and off-farm activities are further irrepressible and diet safe than those that merely depends on survival farming activities.

| Income sources | Total income | Average income | Share of total income |

| Livestock production | 4523701 | 28998.08 | 0.658599 |

| Crop production | 837650 | 5369.551 | 0.121952 |

| Beekeeping | 547459 | 3509.353 | 0.079704 |

| Total farm income | 5908810 | 37876.99 | 0.86025(86.02%) |

| Non-farm income | 939860 | 6024.744 | 0.13683(13.68%) |

| Off-farm income | 20000 | 128.2051 | 0.00291(0.3%) |

| Overall (Farm + Non-farm + Off-farm) income | 6868670 | 44029.94 | 1(100%) |

Source: own survey result, 2021

Table 4: Income sources and shares to total and average income in ETB.

Table 4: Income sources and shares to total and average income in ETB.

Diversification of income in the study site

Agro pastoral households in the study site mainly earn their income from farming, non-farm, and off-farm activities. However, most of the people in the study site are engaged in farming mainly livestock and its product, crop production, and honey beekeeping. Households were classified into three categories based on how they obtained their living. Three income diversification sources were identified among the household namely farming, non-farm, and off-farm activities. The majority of the household's members derived their livelihood from farming. The SID was used in this study to estimate the diversification of income among agro-pastoral households in the Hamer District.

Agro pastoral households in the study site mainly earn their income from farming, non-farm, and off-farm activities. However, most of the people in the study site are engaged in farming mainly livestock and its product, crop production, and honey beekeeping. Households were classified into three categories based on how they obtained their living. Three income diversification sources were identified among the household namely farming, non-farm, and off-farm activities. The majority of the household's members derived their livelihood from farming. The SID was used in this study to estimate the diversification of income among agro-pastoral households in the Hamer District.

Based on Figure 2, sample households with the best-diversified income sources had the biggest index, and those with the smallest sources had the least index. The result indicates that the diversification of income falls between 0 and 0.67 diversity indexes. Of the total sample households, 68 in number, or 43.59% had a diversity index of 0.31-0.61. Based on the result almost half of the sample households diversify their income sources. This implies that those agro-pastoralists diversify their income sources or participate in one to two economic activities. About 47 households or 30.13% had a diversity index of 0.12 to 0.3, and about 10 households or 6.41% had a diversity index between 0.62 and 0.67. About 31 households or 19.87 % had a diversity index of 0-0.11~0. This means that small-holder agro-pastoralists whose Simpson diversity index is equal to zero means households participate in one type of economic activity it may be farming, Non-farming or off-farming. They specialize in one economic or one income-generating activity. The mean income diversification index is 0.31 which is medium in the study site.

The mean intensity of diversification of 0.31 is lower than that observed by Babatunde and Qaim (2009) of 0.479 in Nigeria, and the finding of Agyeman et al. (2014) in Ghana of 0.338. The reason behind this is that most of the people living in the rural area are vulnerable as they depend only on farming-related activities for their livelihood and they are subject to different types of risks (natural disasters) like drought, non-availability of other income sources, etc. Although formal wage employment, rental income, and self-employment income are the new sources of income that emerged in rural households, these activities are mostly run by educated and rich farmers. The medium observed degree of income diversification shows that agro-pastoral households in the Hamer District are medium to low diversified concerning the income-generating activities they engage in. This suggests that on average the respondent in the study site and its members had engaged in nearly minor kinds of income-earning activities instantaneously. These activities were dispersed in two divisions, that is on-farm and non-farm divisions due to the long list of activities identified in the area. On average, a respondent was involved in at least one farming activity and one non-farm activity.

Reason/otives for income diversification

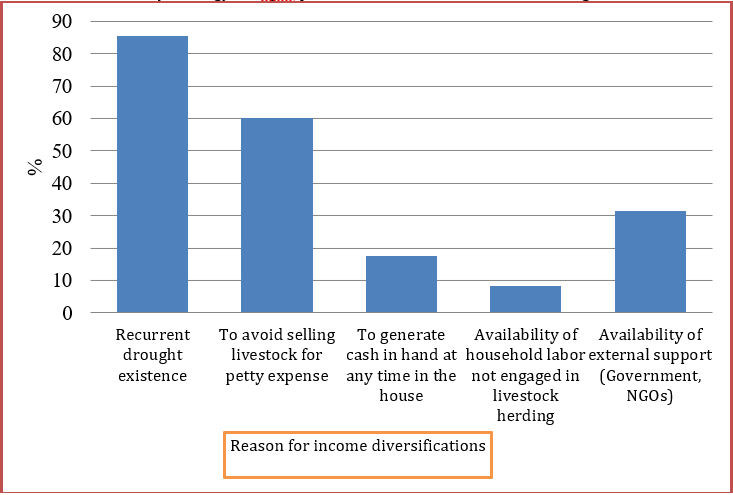

Agro pastoralists of the study site increasingly pursue income diversification strategies to meet consumption needs and to buttress against risky shocks caused by climatic fluctuation, animal disease, market failure, and insecurity. There are five reasons/motives why agro-pastoralists in the study site diversify income. These are the existence of recurrent drought, avoiding livestock selling for petty expense, generating cash in hand at any time in the house, availability of household labor not engaged in livestock herding, and availability of external support (Government, NGOs) in the area. Among the mentioned reason the most important motives were the existence of recurrent drought, avoiding livestock selling for petty expense, and availability of external support (Government, NGOs) raised frequently by respondents 85.3%, 60.1%, and 31.5% respectively. This finding suggests that income diversification is a key strategy for agro-pastoralists in the area to better manage risk.

Agro pastoralists of the study site increasingly pursue income diversification strategies to meet consumption needs and to buttress against risky shocks caused by climatic fluctuation, animal disease, market failure, and insecurity. There are five reasons/motives why agro-pastoralists in the study site diversify income. These are the existence of recurrent drought, avoiding livestock selling for petty expense, generating cash in hand at any time in the house, availability of household labor not engaged in livestock herding, and availability of external support (Government, NGOs) in the area. Among the mentioned reason the most important motives were the existence of recurrent drought, avoiding livestock selling for petty expense, and availability of external support (Government, NGOs) raised frequently by respondents 85.3%, 60.1%, and 31.5% respectively. This finding suggests that income diversification is a key strategy for agro-pastoralists in the area to better manage risk.

Econometric Analysis Result

Left Censored Tobit Regression Model>

Before running the left-censored Tobit regression model, it is compulsory to run a Multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity test. Consequently, the mean Variance Inflation Factor score was 1.32 which is far less than 10 which indicate there is no problem of multicollinearity in the estimation result. Moreover, the contingency coefficient showed there is no association among categorical variables. Gujarati (2003) suggests that a larger value of the Variance Inflation Factor commonly values greater than 10 indicates a serious multicollinearity problem (Appendix 1 and 2). And also the result showed that the probability value of the chi-square statistic is not less than 0.05. Therefore the null hypothesis of constant variance can be not rejected at a 5% level of significance. It implies the absence of heteroscedasticity in the residuals (Appendix 3).

Left Censored Tobit Regression Model>

Before running the left-censored Tobit regression model, it is compulsory to run a Multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity test. Consequently, the mean Variance Inflation Factor score was 1.32 which is far less than 10 which indicate there is no problem of multicollinearity in the estimation result. Moreover, the contingency coefficient showed there is no association among categorical variables. Gujarati (2003) suggests that a larger value of the Variance Inflation Factor commonly values greater than 10 indicates a serious multicollinearity problem (Appendix 1 and 2). And also the result showed that the probability value of the chi-square statistic is not less than 0.05. Therefore the null hypothesis of constant variance can be not rejected at a 5% level of significance. It implies the absence of heteroscedasticity in the residuals (Appendix 3).

The result of the censored Tobit regression estimates of the factors affectingthe level of income diversification (SID) is presented in 8. The model result showed that male-headed households, market distance, frequency of extension contact, farm size, agricultural cooperative membership, and the number of oxen owned significantly affected the level of income diversification (SID) in the study site.

Male-headed households

The sex of the respondent affected the level of income diversification sources, including the choice of income-generating activities (both farm and non-farm) due to socially clear characters, societal movement restrictions, and disparity in possession or right to use assets. From the result of focus group discussion and key informant interview, the above-listed problems hinder female head households to participate in different income-generating activities. The result indicated that male headship has a positive and significant effect on the diversification of income at a 1% probability level. This result agrees with the prior findings of Ellis (1999), Olale et al. (2010), and Demissie and Legesse (2013); Yishak (2017). Thus, keeping other things remains constant the likelihood of income diversification increases by 10.2% when the household head is male (male-headed households). The opposite is true for the female counterparts implying that they are less likely to participate in non-farm income-generating activities. The possible reason is that female heads have more responsibilities in home management (non-income-earning activity) while their counterparts have more tendency of engaging in different non-farm income-generating activities improving their income earnings. Studies indicated that women rarely own land, may have lower education and their access to productive resources as well as decision-making tend to occur through the mediation of men (Demissie and Legesse, 2013).

The sex of the respondent affected the level of income diversification sources, including the choice of income-generating activities (both farm and non-farm) due to socially clear characters, societal movement restrictions, and disparity in possession or right to use assets. From the result of focus group discussion and key informant interview, the above-listed problems hinder female head households to participate in different income-generating activities. The result indicated that male headship has a positive and significant effect on the diversification of income at a 1% probability level. This result agrees with the prior findings of Ellis (1999), Olale et al. (2010), and Demissie and Legesse (2013); Yishak (2017). Thus, keeping other things remains constant the likelihood of income diversification increases by 10.2% when the household head is male (male-headed households). The opposite is true for the female counterparts implying that they are less likely to participate in non-farm income-generating activities. The possible reason is that female heads have more responsibilities in home management (non-income-earning activity) while their counterparts have more tendency of engaging in different non-farm income-generating activities improving their income earnings. Studies indicated that women rarely own land, may have lower education and their access to productive resources as well as decision-making tend to occur through the mediation of men (Demissie and Legesse, 2013).

Extension contacts

At a 5% probability level, the obtained coefficient for extension contact per month was positive and significant. Maintaining other variables constant, agro pastorals' communication with development agents one more time each month by 3.3% enhances the likelihood of revenue diversification. This implies that a rise in the number of extension contacts would result in a rise in the level of income diversification. Contact with extension personnel can inform respondents about more effective and cutting-edge farming methods as well as ways to make money. The outcome also demonstrates that when extension connections rise, so do farm households' levels of income diversification. This result may be attributed to the fact that the presence of extension agents in farming communities has encouraged farm households to take part in other income-generating activities, such as selecting novel crop varieties and livestock species or offering agricultural services (modern technologies like a churning machine) for a living. This study is in line with our prior expectations and the study done by Gebreegziaber et.al (2011) that suggested there is two ways of interpreting the effective participation in agricultural extension program on the diversification of income. The first one is the agricultural extension program expects to increase labor productivity and returns of labor. The second one is the agricultural extension program aims to induce rural households to diversify their income sources. He found that participation in agricultural extension programs had a positive influence on the diversification of income (the dominance of the second effect). Moreover, the study site is drought-prone where farm production is risky and crop failure is frequently exhibited which forces extension works to make frequent contact with reliable farm households. This finding is in line with that of Gebrehiwot and Fekadu (2012) and Yishak et.al. (2014).

At a 5% probability level, the obtained coefficient for extension contact per month was positive and significant. Maintaining other variables constant, agro pastorals' communication with development agents one more time each month by 3.3% enhances the likelihood of revenue diversification. This implies that a rise in the number of extension contacts would result in a rise in the level of income diversification. Contact with extension personnel can inform respondents about more effective and cutting-edge farming methods as well as ways to make money. The outcome also demonstrates that when extension connections rise, so do farm households' levels of income diversification. This result may be attributed to the fact that the presence of extension agents in farming communities has encouraged farm households to take part in other income-generating activities, such as selecting novel crop varieties and livestock species or offering agricultural services (modern technologies like a churning machine) for a living. This study is in line with our prior expectations and the study done by Gebreegziaber et.al (2011) that suggested there is two ways of interpreting the effective participation in agricultural extension program on the diversification of income. The first one is the agricultural extension program expects to increase labor productivity and returns of labor. The second one is the agricultural extension program aims to induce rural households to diversify their income sources. He found that participation in agricultural extension programs had a positive influence on the diversification of income (the dominance of the second effect). Moreover, the study site is drought-prone where farm production is risky and crop failure is frequently exhibited which forces extension works to make frequent contact with reliable farm households. This finding is in line with that of Gebrehiwot and Fekadu (2012) and Yishak et.al. (2014).

Farm Size

The coefficient of farm size was significant at a 1% probability level, implying that agro-pastoralists diversify more into other income-generating ventures as the farm size increases. Keeping other factors constant, a one-hectare increase in the land to be used for livestock or crop production increases the likelihood of income diversification among households by 1.3%. The positive sign indicates that farm households with larger farms or grazing land were more likely to have more diversified sources of income. As a prior expectation, the size of farmland or grazing land used for livestock herding was found to be positive in determining the level of household income diversification. The result confirms the study of Barrett et al., (2001) which indicated that there is a positive relationship between the share of rural income generated from non-farm income sources and the size of landholding, indicating the presence of entry barriers into high-income nonfarm activities for those households that lack such assets. Since, as farm households increase in non-farm activity, their diversification of income might increase. Furthermore, the result suggests that abundant farmland endowment helps households to undertake higher crop production, part of which can be used for livestock production. The result contradicts the study of Ariyo and Mortimore (2011) in Nigeria who reported land ownership in developing countries; particularly in Africa is the most important productive asset available to rural households. Hence, those farmers that have adequate access to land in terms of ownership and size are less likely to diversify into non-farm activities. This could also suggest that diversification into non-farm income sources might be related to a lack of access to land for farming.

The coefficient of farm size was significant at a 1% probability level, implying that agro-pastoralists diversify more into other income-generating ventures as the farm size increases. Keeping other factors constant, a one-hectare increase in the land to be used for livestock or crop production increases the likelihood of income diversification among households by 1.3%. The positive sign indicates that farm households with larger farms or grazing land were more likely to have more diversified sources of income. As a prior expectation, the size of farmland or grazing land used for livestock herding was found to be positive in determining the level of household income diversification. The result confirms the study of Barrett et al., (2001) which indicated that there is a positive relationship between the share of rural income generated from non-farm income sources and the size of landholding, indicating the presence of entry barriers into high-income nonfarm activities for those households that lack such assets. Since, as farm households increase in non-farm activity, their diversification of income might increase. Furthermore, the result suggests that abundant farmland endowment helps households to undertake higher crop production, part of which can be used for livestock production. The result contradicts the study of Ariyo and Mortimore (2011) in Nigeria who reported land ownership in developing countries; particularly in Africa is the most important productive asset available to rural households. Hence, those farmers that have adequate access to land in terms of ownership and size are less likely to diversify into non-farm activities. This could also suggest that diversification into non-farm income sources might be related to a lack of access to land for farming.

Agricultural cooperative membership

The coefficient of agricultural cooperative membership (goat fattening cooperatives, gum and incense collection cooperatives, etc.)was significant at a 5% probability level, implying that agro-pastoralists diversify more into other income-generating projects as the agricultural cooperative membershipincreases. The likelihood of income diversity among households in agricultural cooperatives improves by 9.7% with each additional household member, all other things being equal. The good news is that farm households were more likely to have more varied sources of income if they participated more actively in agricultural cooperative membership. Being a member of an agricultural cooperative can increase agro-pastoralists' access to financial resources and operate as a forum for the sharing of ideas that can boost both their farming and non-farming endeavors. As a result, it broadens the range of revenue sources available to agro-pastoralists in the research area.

The coefficient of agricultural cooperative membership (goat fattening cooperatives, gum and incense collection cooperatives, etc.)was significant at a 5% probability level, implying that agro-pastoralists diversify more into other income-generating projects as the agricultural cooperative membershipincreases. The likelihood of income diversity among households in agricultural cooperatives improves by 9.7% with each additional household member, all other things being equal. The good news is that farm households were more likely to have more varied sources of income if they participated more actively in agricultural cooperative membership. Being a member of an agricultural cooperative can increase agro-pastoralists' access to financial resources and operate as a forum for the sharing of ideas that can boost both their farming and non-farming endeavors. As a result, it broadens the range of revenue sources available to agro-pastoralists in the research area.

Market distance

At a 5% probability level, the market distance between agro pastoral households' homestead and activities that change their way of life hurts their potential to diversify their income. Citrus paribus, the average marginal effect predicts a 3.9% fall in the likelihood of income diversification for every kilometer the market distance increases. In other words, proximity to market hubs facilitates access to additional revenue by offering opportunities for employment off-farm, as well as simple access to participation in different activities and marketing agricultural or non-agricultural products. This outcome is consistent with Lesego's (2017) discovery that there is a positive and significant correlation between non-farm diversification and market distance, as doing so enables households to engage in non-farm activities.

At a 5% probability level, the market distance between agro pastoral households' homestead and activities that change their way of life hurts their potential to diversify their income. Citrus paribus, the average marginal effect predicts a 3.9% fall in the likelihood of income diversification for every kilometer the market distance increases. In other words, proximity to market hubs facilitates access to additional revenue by offering opportunities for employment off-farm, as well as simple access to participation in different activities and marketing agricultural or non-agricultural products. This outcome is consistent with Lesego's (2017) discovery that there is a positive and significant correlation between non-farm diversification and market distance, as doing so enables households to engage in non-farm activities.

The findings published by Oluwatayo (2009), Demissie and Legesse (2013), Teshome and Edriss (2013), Fufa et al. (2018), Yisihake and Abebe (2016), and Yishak (2017) are all in agreement with this result (2017). This inverse association suggests that non-farm and off-farm activity participation is less likely in households located further from the market. The rationale might be that families near market hubs don't have to pay as much to take advantage of market incentives for income diversity. It stands to reason that agro pastorals may be dissuaded from engaging in such activities if they are unable to sell the products of their non-farm activities on the market. Additionally, local petty trade and other typical non-farm and off-farm businesses need a quick market to expand production. As a result, a far distance from the closest market diminishes the income index's diversification. This study showed that in all situations of rural income diversification strategies to earn revenue from non-farm employment in addition to farming income, road infrastructure is the most significant element in participation of non-farm activities and raising the amount of income diversification.

Number of oxen/drought power

At a 5% likelihood level, household draught power ownership influenced the diversification of household income positively. This suggests that, while holding other variables equal, the likelihood of household income diversification increased by 1.18%, and the number of homes with draught power ownership increased by one. Draught power ownership is associated with livestock size and also a proxy to wealth as well; those with large draught power size have the option to stay at on-farm income sources and also may be initiated to rent out as drought power or oxen trading. Another possible reason for this is that when households own oxen it encourages crop farming as draught power is important for farming in the study site and also there is a practice of oxen renting daily for plows. This finding disagrees with that of Yisihake and Anupama (2018), who found that having access to an animal plow encourages rural farm households to involve in farming as opposed to other off-farm income-generating activities.

At a 5% likelihood level, household draught power ownership influenced the diversification of household income positively. This suggests that, while holding other variables equal, the likelihood of household income diversification increased by 1.18%, and the number of homes with draught power ownership increased by one. Draught power ownership is associated with livestock size and also a proxy to wealth as well; those with large draught power size have the option to stay at on-farm income sources and also may be initiated to rent out as drought power or oxen trading. Another possible reason for this is that when households own oxen it encourages crop farming as draught power is important for farming in the study site and also there is a practice of oxen renting daily for plows. This finding disagrees with that of Yisihake and Anupama (2018), who found that having access to an animal plow encourages rural farm households to involve in farming as opposed to other off-farm income-generating activities.

| Explanatory variables | dy/dx | Coefficient | Std.err | t- value | p>|t| |

| Sex(male) | 0.1017 | 0.1128*** | 0.0374 | 3.01 | 0.003 |

| Age | 0.0020 | 0.0022 | 0.0019 | 1.13 | 0.261 |

| Education | 0.0057 | 0.0063 | 0.0236 | 0.27 | 0.789 |

| Oxen No | 0.0118 | 0.0131** | 0.0065 | 2.03 | 0.045 |

| Market distance | -0.0389 | -0.0432** | 0.0199 | -2.18 | 0.031 |

| Farm size | 0.0126 | 0.0139*** | 0.0053 | 2.64 | 0.009 |

| Adult equivalent | 0.0056 | 0.0062 | 0.0066 | 0.95 | 0.346 |

| Cooperative(yes) | 0.0952 | 0.1076** | 0.0457 | 2.35 | 0.020 |

| Access to information(yes) | -0.0303 | -0.0336 | 0.0339 | -0.99 | 0.324 |

| Credit use (yes) | -0.0188 | -0.0209 | 0.0387 | -0.59 | 0.590 |

| TLU | 0.0006 | 0.0007 | 0.0008 | 0.78 | 0.438 |

| Extension contact | 0.0329 | 0.0366** | 0.0142 | 2.58 | 0.011 |

| Constant | - | -0.2250 | 0.1242 | -1.81 | 0.072 |

Total observation = 156, LR chi2 (12) = 44.28, Prob > chi2 = 0.0000, Pseudo R2 =1.3756, Log pseudo likelihood = 6.04518. ***, ** and * indicates statically significant at 1 and 5% respectively.

Table 5: Left censored Tobit regression model results.

Table 5: Left censored Tobit regression model results.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions

The livelihood of pastoral and agro-pastoral society does not only depend on the rearing of livestock and crop production, but it also relays on different survival activities that substitute the accumulation of additional capital. Although the primary focus of agro-pastoralists' livelihood is livestock rising, they are constantly seeking new ways to make a living to lessen the negative effects of natural disasters. Many rural households work beyond only raising livestock and growing crops to generate revenue. In general, households are divided into three groups according to the sources of revenue they produce. Farm, off-farm, and non-farm revenue are the main sources of income. The revenue distribution among rural households shows that agricultural production comes in second, followed by the sale of livestock and its products. This demonstrates that raising livestock is a significant contributor to the study site's about 65.86% of total household income. According to the SID results, the average level of income for the diversification index in the study area is 0.31, which is medium to low. Amounts of families classified as non-diversified, low, medium, and high levels of diversity were 19.87%, 30.13%, 43.59%, and 6.41%, respectively. In general, the results suggest a substantial proportion of farm income to household total income and a lack of effective income diversification in the area. Agro pastoralists have been constrained by various factors while accessing the diversification of income. A frequently cited reasons are shortage of starting money, fear of losing land involved in activities outside agriculture, do not skill or knowledge, and scarcity of labor. A Tobit regression model was employed to determine factors affecting the diversification of income among the farm households." The result of the model indicated that in male-headed households; the number of oxen/drought power, market distance, farm size, agricultural cooperative membership, and extension contact had a statistically significant effect on households' diversification of income.

The livelihood of pastoral and agro-pastoral society does not only depend on the rearing of livestock and crop production, but it also relays on different survival activities that substitute the accumulation of additional capital. Although the primary focus of agro-pastoralists' livelihood is livestock rising, they are constantly seeking new ways to make a living to lessen the negative effects of natural disasters. Many rural households work beyond only raising livestock and growing crops to generate revenue. In general, households are divided into three groups according to the sources of revenue they produce. Farm, off-farm, and non-farm revenue are the main sources of income. The revenue distribution among rural households shows that agricultural production comes in second, followed by the sale of livestock and its products. This demonstrates that raising livestock is a significant contributor to the study site's about 65.86% of total household income. According to the SID results, the average level of income for the diversification index in the study area is 0.31, which is medium to low. Amounts of families classified as non-diversified, low, medium, and high levels of diversity were 19.87%, 30.13%, 43.59%, and 6.41%, respectively. In general, the results suggest a substantial proportion of farm income to household total income and a lack of effective income diversification in the area. Agro pastoralists have been constrained by various factors while accessing the diversification of income. A frequently cited reasons are shortage of starting money, fear of losing land involved in activities outside agriculture, do not skill or knowledge, and scarcity of labor. A Tobit regression model was employed to determine factors affecting the diversification of income among the farm households." The result of the model indicated that in male-headed households; the number of oxen/drought power, market distance, farm size, agricultural cooperative membership, and extension contact had a statistically significant effect on households' diversification of income.

Agro pastoralists of the study site increasingly pursue income diversification strategies to meet consumption needs and to buttress against risky shocks caused by climatic fluctuation, animal disease, market failure, and insecurity. These are the existence of recurrent drought, avoiding livestock selling for petty expense, generating cash in hand at any time in the house, availability of household labor not engaged in livestock herding, and availability of external support (Government, NGOs) in the area. Among the mentioned reason the most important motive for avoiding livestock selling for petty expense, availability of external support (Government, NGOs), and the existence of recurrent drought were raised frequently by respondents. The importance of agro-pastoralists' involvement in income diversification initiatives for a maintainable agro pastoral livelihood can’t be overstated. It is evident that practically all agro pastoral households in the research site engage in fewer non-farm activities to supplement their revenue from raising livestock; as a result, broadening sources of their income and enhancing their standard of living is crucial.

Recommendation

To make considerable improvement in the diversification of income status in Hamer District the following measures and actions should be taken by household heads, the administration of the region and District, and national and international organizations. The possible areas of intervention that arise from the results of this study are presented as follows:

To make considerable improvement in the diversification of income status in Hamer District the following measures and actions should be taken by household heads, the administration of the region and District, and national and international organizations. The possible areas of intervention that arise from the results of this study are presented as follows:

To enhance the diversification of income, the government should continue its efforts in forming non-farm and off-farm business cooperatives to generate income-earning opportunities in the rural areas and support the agro-pastoralists to enhance non-farm and off-farm business activities productivity through supportive policies including input provision and creating a market for their product. Due to its lack of involvement in the District, the Hamer District office of the agricultural cooperative may be tasked with offering guidance and training to rural households as they establish non-farm and off-farm cooperatives. Because women's engagement in non-farm and off-farm activities is low in the research site, the government and other responsible entities develop the necessary measures to raise awareness within the community. These tactics are especially important for non-farm and off-farm activities. Moreover, extension service delivery should be strengthened in the Hamer District by building the capacity of extension officers through training, provision of logistics as well as incentives. This is expected to result in the provision of efficient extension services delivery to farm households. However, extension service delivery on non-farm and off-farm activities was very weak in the area. Hence, government and other responsible bodies should design strategies and plan to give extensions for non/off the farm and provide logistics to participate agro pastorals on non-farm and off-farm activities to mitigate risks in agro-pastoral areas. Maintaining sustainable livelihood of agro pastorals in the study site, and involving agro pastorals in non-farm and off-farm income sources are crucial. Enhance these income sources, especially road accessibility play a vital role in facilitating access to markets in the study site. Hence, need to provide more rural roads and rehabilitate eroded ones to reduce the high transaction cost of buying from or selling to markets, as transaction cost reduces the returns from market sales. This will encourage the development of the rural road to facilitate agro-pastoral participation in non-farm and off-farm economic activities. Therefore, government policy should pay more attention to infrastructure to reduce the entry barriers and facilitate easier access to non-farm and off-farm activities.

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly indebted to South omo zone Livestock and Fisheries department for giving this chance and we also sincerely thank local communities in our research area, Hamer district and all the field assistants for their valuable efforts.

The authors greatly indebted to South omo zone Livestock and Fisheries department for giving this chance and we also sincerely thank local communities in our research area, Hamer district and all the field assistants for their valuable efforts.

References

- Agyeman, B. A. S, Asuming-Brempong, S. and Onumah, E.E (2014). Determinants of Income diversification of farm households in the western region of Ghana. Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture, 53(1): 55-72.

- Algaga, B, and Sisay, D (2020). Analysis of Income Diversification and Livelihood Strategies Among Pastoral and Agro-pastoral Households in Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Investment and management. 9 (3), 72-79.

- Amanze, J, Ezeh, C. and Okoronkwo, M (2011). The pattern of income diversification strategies among rural farmers in Nnewi North local government area of Anambra state. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development. V.6, No.5, (2015). 2222-2855.

- Ariyo, J.A, and Mortimore, M (2011). “Land Deals and Commercial Agriculture in Nigeria: The New Nigerian Farms in Shonga District, Kwara State.” Paper presented at the International Conference on Global Land Grabbing, 6–8 April. Sussex, UK: Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex

- Asmera A, Mekete G, Dawit D, Kutoya K. (2020). Value Chain Analysis of Goat in South Omo Zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development. 7(1): 907-919.