Research Article

Volume 4 Issue 2 - 2022

Field Evaluation of 25 Sweet Potato Genotypes for Qualitative and Quantitative characters, Biotic Reactions and starch Contents in UYO, Southeastern Nigeria.

1Department of Crop Science, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Uyo, Akwa Ibom State

2National Root Crops Research Institute, Umudike, Abia State, Nigeria

2National Root Crops Research Institute, Umudike, Abia State, Nigeria

*Corresponding Author: Bassey E. E, Department of Crop Science, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Uyo, Akwa Ibom State.

Received: April 08, 2022; Published: April 18, 2022

Abstract

Field experiment was conducted at the National Cereals Research Institute, Badeggi, Uyo Outstation, Nigeria in 2021 cropping season. The aim was to evaluate 25 sweet potato genotypes for qualitative and quantitative characters, biotic reactions and starch contents as guide to improvement. The experiment which occupied a land areas of 75 m x 11 m was laid out in a randomized complete block design and replicated three times. Twenty-nine characters were studied. Significant differences (p<0.05) were observed in all the quantitative characters. The genotype 87/OP/195 was superior in ten characters: root size, root form, longest storage roots (cm), resistance to weevils, number of established stands per plot, number of harvested stands per plot, number of commercial storage roots per plot, weight of commercial storage roots (kg), yield of commercial storage roots (tha-1) and total storage root yield (tha-1), followed by PGA 14442-1 in nine characters: root size, root form, resistance to leaf spot, number of non-commercial storage roots, weight of non-commercial storage roots (kg), yield of non-commercial storage roots (tha-1), harvest index (%), yield of commercial storage roots (tha-1) and total storage root yield (tha-1), Butter milk was ranked second in commercial storage root number, third in weight of commercial storage roots (kg), weight of non-commercial storage roots (kg), resistance to weevils, yield of commercial storage roots (tha-1) and total root storage yields (tha-1). while PGA 14011-43 was rated fourth in resistance to sweet potato virus disease, number of commercial storage roots, weight of commercial storage roots (kg), non-commercial storage root yield (tha-1) and total storage root yield(tha-1). The four sweet potato genotypes were rich in β-carotene. The genotype, 87/OP/195 and PGA 14442 could be distributed to farmers in the area for cultivation while the four candidate genotypes could be incorporated into multi-location trials and improvement programmes to produce hybrid varieties for the area.

Keywords: Biotic Reaction; Qualitative characters; Quantitative characters; Starch content; Sweet potato

Introduction

Sweet potato is a perennial root crop usually cultivated as annual crop which belongs to the bindweed or morning glory family Convolvulaceae (Tortoe, 2010). It is a widely grown important staple crop in most parts of tropical and subtropical regions of the world (ICAR, 2007), being cultivated in more than 100 countries (Woolfe, 1992; Bassey, 2021). Sweet potato is among the most important versatile and underutilized food crops, grown mainly for its large, sweet tasting, starchy tuberous roots (Tortoe, 2010). Among the tuber crops grown in the world, sweet potato ranks second after cassava (Ray and Ravi, 2005), seventh among the world food crops after wheat, rice, maize, potato, barley and cassava (Gundadhur, 2012), third in value of production and fifth in caloric contribution to human diet (Bouwkamp, 1985; Antiaobong et al., 2009). It has been considered very important in providing nutritional security particularly in agriculturally backward areas (Srinivas, 2009) with poor soils (Nwankwo et al., 2014).

Wide variability exists in sweet potato both in the morphological characters and yield (Alam et al., 1998; Bassey, 2021). The crop varies in growth habit (spreading, extremely spreading, erect and semi-erect), skin colour (white, light purple, purple, pink) and flesh colour (white, cream, yellow, pink, light purple, purple and red) (Nwankwo et al., 2014). The leaf shape ranges from entire to deeply lobed (Nwankwo et al., 2012). Significant progress has been made in the breeding and selection of sweet potato for high root yield, early maturity and fodder yields for mixed crop – livestock farming systems (Shumbusha et al., 2019). Selection for high yielding (root tubers and fodder) genotypes now constitutes an important aspect of improvement in sweet potato (Urgessa et al., 2014; Nwankwo and Bassey, 2021). Its high photosynthetic efficiency, high energy yielding potential per unit area per time (Nedunchezhiyan et al., 2014) and early maturity (Antiaobong et al., 2009) make sweet potato an ideal crop for rural poor farmers. The vine tips and leaves are excellent vegetables for man and nutritious green fodder for cattle (Nedunchezhiyan et al., 2012), being rich in pro-vitamin A, vitamins B and C as well as minerals such as calcium, iron, potassium and sodium (Antiaobong et al., 2009). The tubers can be reconstituted into foofoo, or blended with other carbohydrate flour sources especially wheat, and used in baking bread, cakes and biscuits (Bassey, 2021). It is now used as a major source of industrial starch for pharmaceutical adhesives, textile, paper and alcohol production (Woolfe, 1992; Bassey, 2021). The tubers may be fried into chips, boiled and consumed with sauces and as snack with beverage or milled into flour and mixed with millet and sorghum or processed into local foods (Bassey, 2021).

However, the major constraints to sweet potato production are low yields per unit area, especially from marginal soils, unavailability of adequate seed vines during the growing periods and pests and diseases (Nwankwo et al., 2021). The use of infected sweet potato seed vines with sweet potato virus disease, leaf spot and alternalia results in smaller, low marketable storage roots (Nwankwo and Njoku, 2019). High quality seed vine is capable of improving growth vigour, vegetative yield and storage root yields and there is need for selection of sweet potato genotypes for both high storage root tuber and quality seed vine yields (Nwankwo and Bassey, 2021). China accounts for the highest sweet potato production in the world, followed by Nigeria and Uganda (Bassey, 2021). The objective of this study was to evaluate 25 sweet potato genotypes for qualitative and quantitative characters, biotic reactions and starch content in humid environment of Uyo, southeastern Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

Field experiments were conducted at the National Cereals Research Institute, Uyo Outstation and Farmers Demonstration Plot, in Owot-Uta, Ibesikpo-Asutan Local Government Area of Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria in 2021 cropping season. The aim was to evaluate 25 sweet potato genotypes for qualitative and quantitative characters, biotic reactions and starch contents as a guide to further improvement of the crop. The area lies within latitude 05°16' and 05° 27' north and longitude 07° 27' and 07° 56' east of the Greenwich Meridian and altitude 45 m above sea level. The area is a fairly flat terrain which receives average rainfall of over 2500 mm with daily photoperiod of 3.5 h. The temperature is generally high ranging from 23°C to 34°C throughout the year. Mean relative humidity is about 78%, with the lowest (70.4%) and highest (86.6%) values in January/December and July, respectively (Umoh, 2013). The soil is a typical acid sand (Ekpeh, 1994). The land was under fallow for two years before being put to the experiments. The vegetation consisted mainly of Panicum maximum, Paspalum conjugatum, Cyperus spp, Aspilia latifolia, Commelina nodiflora, Ipomoea involucrata, Icacina trichantha, Caladium bicolour and Peuraria phaseoloides, among others.

Twenty-four (24) sweet potato genotypes were collected from the National Root Crops Research Institute (NRCRI), Umudike Abia State, Nigeria, namely: PGA 14008-9, Obare, Kwara, NAN, Cri-Apomuden, PG 17362-NI, 87/OP/195, PGN16021-39, CEMSA 74-228, TIS87/0087 (check), PGA 14442-1, Butter milk, PGA 14011-43, PGA 14398-4, Cri-Dadanyuie, PGA 14372-3, Cri-Okumkom, PO3/35, PGA 14351-4, UMUSPO/3 (check), Tu-Purple, Nwoyorima, PO3/116 and Uyo Local (adaptive cultivar obtained from sweet potato farmers). Land area of 75m x 11 m was laid out in a randomized complete block design and replicated three times. The land was mechanically ploughed, harrowed and ridged 1 m apart. Healthy sweet potato vine cuttings measuring 30 cm long with at least 6 nodes were planted on the crest of the ridges at 30 cm intra-row and 100 cm inter-row. Each plot consisted of three ridges. The sweet potato vines were planted sole. All the 25 sweet potato genotypes were assigned to the plots randomly. Thirty (30) healthy sweet potato vines were planted per plot, giving 30,000 plants per hectare. Weeding was manually done two times to prevent competition with weeds. Fertilizer NPK (15:15:15) was applied at 400kg/ha to improve the nutrient status of the soil.

Four plants were randomly selected and tagged at the centre of each plot for data collection. Qualitative and quantitative characters, biotic reaction and starch content studied were: Number of plant established per plot, vigour, number of plants harvested per plot, number of commercials storage roots, number of non-commercial storage roots, weight of commercial storage roots (kg), weight of non-commercial storage roots (kg), weight of vines (kg), longest storage roots (cm), width of longest storage roots (cm), ground cover (%), harvest index (%), skin colour, flesh colour, root size, root form, biotic reactions (leaf spot at 4 and 12WAP, SPVD at 4 and 12 WAP, Alternalia at 4 WAP, holes and cracks per plot), moisture content (%) and starch contents (%), fodder yields (tha-1) and storage root yields (tha-1).

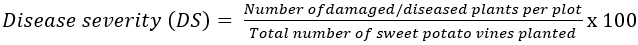

All the quantitative data were subjected to Analysis of Variance and the means separated with Duncan Multiple Range Test at 5% probability level. Rating scale (1 – 9) (CIP, 2020; Nwankwo et al., 2021) was used to determine the severity of sweet potato virus disease (SPVD), where 1 = no virus symptoms, 2 = unclear virus symptoms, 3 = clear virus symptoms, (<5% of plant/plot), 4 = clear virus symptoms (6 – 33% of plants/plot), 5 = clear virus symptoms (34 – 66% of plants/plot), 7 = clear virus symptoms (67 – 99% of plants/plot), 8 = clear virus symptoms (all plants/plot affected, but not stunted), 9 = severe virus symptoms on all the plants and stunted). Similarly, alternalia symptoms was determined one month after planting and recorded in scores from 1 – 9, where 1, indicates no symptoms, 2 = unclear symptoms, 3 = clear symptoms at <5% per plot, 4 = clear symptoms at 6 – 15% of plants per plot, 5 – clear symptoms at 16 to 33% of plants per plot (less than 1/3), 6 = clear symptoms at 34 – 55% of plants per plot (more than 1/3, less than 2/3), 7 – clear symptoms at 67 to 99% of plants per plot (2/3 to almost all), 8 = clear symptoms, all plants affected but not fully defoliated; 9 = severe symptoms, all plants per plot affected and fully defoliated. Leaf spot was also assessed using the scale 1 – 9, where 1 = no symptoms, 2 = symptom present, 3 = symptom very mild, 4 = symptom mild, 5 = symptom very moderate, 6 = symptom moderate, 7 = symptom severe, 8 = symptom very severe and 9 = plants almost dead (Nwankwo et al., 2021). Similarly, plant vigour was determined on rating scale 1 – 9 (CIP, 2020), where 1 = nearly no vines, 2 = weak vines, thin stems, very long internodes distances, 3 = weak to medium strong vines, medium thick stems, medium internodes, 5 = medium strong vines, thick vines, long internode distances, 6 = medium strong vines, thick stems, medium internode distances, 7 = strong vines, thick stems, short internode distances and medium – long vines, 8 = strong vines, thick stems, short internode distances, long vines, and 9 = very strong vine length, thick stem, short internode and very long vines. Disease severity was determined as described by Stathers et al. (2005), thus

The values derived were compared with the percentages in the rating scale and appropriate scale assigned to them. Munsen Colour Chart was used for the determination of skin colour where 1 = white, 2 = cream, 3 = yellow, 4 = orange, 5 = brownish orange, 6 = pink, 7 = red, 8 = purple red, 9 = dark purple. For flesh colours were 1 = white, 2 = cream, 3 = dark cream, 4 = pale yellow, 5 = dark yellow, 6 = pale orange, 7 = intermediate orange, 8 = dark orange and 9 = purple (Nwankwo et al., 2021). Plant habit and ground cover of the sweet potato genotypes were determined using the scale 1 – 5 (Nwankwo et al., 2021), where 1 = 1 - 25%; 2 = 26 – 49% (<50%) ground cover; 3 = 50 – 75% ground cover; 4 = 76 – 90% ground cover, while 5 = 91 – 100% ground cover (i.e. >90%). Visual observation by five persons were recorded and the mean used in assigning them to appropriate rating scale.

Sweet potato storage roots below 100g were considered as non-commercial storage roots, while those with 100g and above were graded as commercial storage roots (Nwankwo and Bassey, 2021). Root size and root form were assessed based on inspection of the harvested roots, where 1 = Excellent, 2 = Very good, 3 = Good, 4 = Fairly good, 5 = Fair, 6 = Poor, 7 = Very poor, 8 = Extremely poor, 9 = Terrible (Nwankwo et al., 2021). Samples of the sweet potato genotypes were taken to the University of Uyo Agronomy Laboratory for the determination of moisture and starch contents (%).

Results

Table 1 shows the number of plants (established) per plot, growth vigour scores, number of plants harvested per plot, number of commercial storage roots, number of non-commercial storage roots, weight of commercial storage roots/plot (kg), weight of non-commercial storage roots/plot (kg), weight of vines per plot (kg), longest storage roots (cm), width of longest storage roots (cm), ground cover (%) and harvest index. Significant differences (p<0.05) were observed for all the characters. The highest number of stands per plot was recorded in 87/OP/195 (14), followed by PG17265-NI (11) and Nwoyorima (10) while the lowest was Cri-Dadanyuie (4). Differences in growth vigour were observed among the sweet potato genotypes with the highest vigour of 9 recorded for PGA 14008-9, followed by 8 genotypes with growth vigour 8, namely Kwara, TIS 87/0087 (check), PGA 14442-1, PGA 14011-43, P03/35, TU-purple, PG 17265-NI and Nwoyorima while the lowest vigour score of 3 was recorded for NAN. The highest number of plants harvested per plot was produced by 87/OP/195 (12), followed by Tu-purple (10) and PG17265-NI (9) and UMUSPO/3 (9), while the lowest number (3) was produced by NAN. Similarly, the highest number of commercial storage roots was produced by 87/OP/195 (25), followed by Butter milk (18), PG4011-43 (15), while 8 genotypes produced no commercial storage roots, namely Kwara, PGN16021-39, Cemsa 74-228, PGA14398-4, P03/35, Tu-purple, PG 17265-NI and P03/116. Number of non-commercial storage roots varied significantly (P<0.05), with the highest (41.5) being produced by PGA 14442-1, followed by PGA 14372-3 (33.3), 87/OP/195 (27), PGA 14008-9 (24.5) and PGA 14011-43 (23.3), while Kwara produced no non-commercial storage roots. The genotype 87/OP/195 produced the highest fresh weight of commercial storage roots (11.5 kg), followed by PGA 14442-1 with 7.0 kg, butter milk (5.6 kg), PGA 14011-43 (4.7 kg), local best (3.5 kg), while seven sweet potato genotypes recorded zero (0) fresh weight of commercial storage roots. The highest fresh weight of non-commercial storage roots (kg) was produced by PGA14442-1 (5.5 kg), followed by PGA 14011-43 (4.9 kg), CEMSA 74-228 (4.1 kg), PGA 14398-4 (4.0 kg), and Butter milk (3.7 kg) while Kwara produced no non-commercial roots and consequently no storage root yield (Table 1a).

The highest storage root yields of 48.9 (tha-1) was produced by 87/OP/195, followed by PGA 14442-1 (41.6 tha-1), PGA 14011-43 (31.9 tha-1) and Butter milk (30.999 tha-1), which were greater than the national checks, UMUSPO/3(17.3 tha-1) and TIS 87/0087 (11.6 tha-1) and local check (18.6 tha-1) while Kwara produced no storage root yield (Table 1b).

Weight of vines per plot differed significantly (p<0.05) among the sweet potato genotypes in the area. The sweet potato genotype with the highest fresh weight of vines was P03/35 (7.8 kg), followed by Tu-purple (6.2 kg), Nwoyorima (5.6 kg) and PO3/116 (4.1 kg), while the lowest vine weight (0.3 kg per plot was produced by Cri-Apomudem and PG17362-NI (Table 1b). The highest forage (fodder yield of 259.9 Nwoyorima (186.6 tha-1) and PO3/116 (153.3 tha-1), while the least fodder yields of 9.9 tha-1 were recorded on Cri-Apomuden and PG 17362-NI. Sweet potato genotypes with the greatest ground cover of 100% and rated 5, were PG 17265-NI (100%) and Nwoyorima (100%) while PGA 14442-1 and PGA 14011-43 produced 95% groundcover, followed by genotypes with groundcover of 76 – 90%, namely TIS 87/0087 (90%), Butter milk (90%) and P03/116 (90%), local best (85%), UMUSPO/3 (85%), PGA 14372-3 (83%) and P03/35 (80%). Eight (8) sweet potato genotypes fell into the group 50 – 75% ground cover, namely PG 17362-NI (75%), PGA 14351-4 (75%), Cri-Okumkom (70%), PGA 14398-4 (65%), Cri-Apomuden (65%), Obare (60%), Cri-Dadanyuie (50%) and Cemsa 74-228 (50%), while 3 genotypes were grouped under 26 – 49% (<50%) ground cover, namely PGN 16021-39 (45%), 87/OP/195 (45%) and PGA 14008-9 (43%). Consequently, the sweet potato genotypes were described as extremely spreading – ES (<90%), Spreading-S (76 – 90%), Semi-erect-SE (50 – 75%), Erect-E (<50%), respectively.

The result (Table 1b) shows variability in harvest index (%) among the 25 sweet potato genotypes. The highest harvest index of 25.0 was produced by PGA 14442-NI, followed by 87/OP/195 (12.0), Cemsa 74-228 (9.2), Cri-Apomuden (7.6) and PGA 14011-43 (5.7). However, harvest index (%) was not determined for two sweet potato genotypes namely, Kwara and NAN since they recorded no storage roots.

Table 2 shows the qualitative traits of the 25 sweet potato genotypes (skin colour, flesh colour, root size, root form) and biotic reactions (cracks, holes, leafspots, sweet potato virus disease and alternalia) and starch contents. The skin colours of the sweet potato genotypes varied from cream, orange, pink, purple and purple red. Cri-okumkom was creamy while four sweet potato genotypes were yellowish (PGN 16021-39, PGA 14442-1, local best and Nwoyorima). The predominant skin colour was pink, associated with 14 sweet potato genotypes, namely: PGA 14008-9, Obare, Cri-Apomuden, PG 17362-NI, 87/OP/195, Cemsa 74-228, TIS 87/0087 (check), PGA 14442-1, PGA 14398-4, Cri-Dadanyuie, P03/35, UMUSPO/3 (check), Tu-purple and PG 17265-NI, while two were orange, namely PGA 14011-43 and PGA 14351-4. The skin colour of PG14372-3 was purple while that of P03/116 was purple red. Similarly, flesh colour of the sweet potato genotypes varied from white, cream, yellow, orange, pale orange, pink and dark purple. One sweet potato genotype was white, namely PG

| S/No | Sweet potato | Number planted/plot | Number established per plot | Vigour score | Number harvested per plot | Number of commercial storage roots per plot | Number of non-commercial roots per plot | Weight of commercial storage roots/plot (kg) | Weight of non-commer-cial roots/plot (kg) |

| 1 | PGA 14008-9 | 30 | 7d | 9 | 7c | 1g | 24.5d | 0.2i | 2.4d |

| 2 | OBARE | 30 | 7d | 7 | 7c | 1g | 4.5k | 0.2i | 0.2g |

| 3 | KWARA | 30 | 7d | 8 | 6d | 0h | 0.0m | 0j | 0h |

| 4 | NAN | 20 | 5e | 3 | 3e | 1g | 15.0g | 0.2i | 0.6f |

| 5 | CRI-APOMUDEN | 20 | 7d | 7 | 5d | 3f | 21.5e | 0.9g | 1.4e |

| 6 | PG17362-NI | 20 | 7d | 7 | 5d | 3f | 10.0h | 0.4h | 1.1e |

| 7 | 87/OP/195 | 20 | 14a | 7 | 12a | 25a | 27.0c | 11.5a | 3.2c |

| 8 | PGN 16021-39 | 30 | 9c | 7 | 9b | 0h | 12.0h | 0j | 1.3e |

| 9 | CEMSA 74-228 | 30 | 9c | 6 | 8c | 0h | 23.0d | 0j | 4.1b |

| 10 | TIS 87/0087 (CHECK) | 30 | 8c | 8 | 8c | 1g | 18.6f | 0.5h | 3.0c |

| 11 | PGA 14442-1 | 30 | 8c | 8 | 7c | 13d | 41.5a | 7.0b | 5.5a |

| 12 | BUTTER MILK | 30 | 6d | 7 | 6d | 18b | 23.0d | 5.6c | 3.7bc |

| 13 | PGA 14011-43 | 20 | 8c | 8 | 5d | 15c | 23.3d | 4.7d | 4.9b |

| 14 | PGA 14398-4 | 20 | 6d | 6 | 6d | 0 | 11.5h | 0j | 1.1e |

| 15 | CRI-DA DANYUIE | 20 | 4e | 7 | 4e | 3f | 2.5l | 2.1f | 0.5f |

| 16 | LOCAL BEST | 30 | 6d | 7 | 6d | 10d | 20.6e | 3.5e | 2.1d |

| 17 | PGA 14372-3 | 30 | 6d | 7 | 6d | 7e | 33.3b | 1.8f | 4.0bc |

| 18 | CRI-OKUMKOM | 30 | 6d | 7 | 6d | 5f | 7.0j | 1.7f | 1.0e |

| 19 | PO3/35 | 20 | 6d | 8 | 6d | 0h | 7.3j | 0j | 0.2g |

| 20 | PGA 14351-4 | 20 | 6d | 7 | 6d | 1g | 6.0j | 0.6h | 0.6f |

| 21 | UMUSPO/3 (CHECK) | 30 | 9c | 6 | 9b | 4f | 14.5g | 2.6f | 2.6d |

| 22 | TU-PURPLE | 20 | 9c | 8 | 10b | 0h | 11.0h | 0j | 0.6f |

| 23 | PG 17265-NI | 30 | 11b | 8 | 9b | 0h | 9.0i | 0j | 1.5e |

| 24 | NWOYORIMA | 30 | 10b | 8 | 8c | 14c | 7.5j | 2.0f | 2.0d |

| 25 | PO3/116 | 30 | 9c | 7 | 7c | 0 | 6.6j | 0j | 1.0e |

1 = Incidence; S = Severity; SPVD = Sweetpotato Virus Disease

Table 1(a): Number of established plants, growth vigour, number harvested per plot, number of commercial and non-commercial storage roots and weights of commercial and non-commercial storate roots of sweet potato genotypes in Uyo, Southeastern Nigeria.

Table 1(a): Number of established plants, growth vigour, number harvested per plot, number of commercial and non-commercial storage roots and weights of commercial and non-commercial storate roots of sweet potato genotypes in Uyo, Southeastern Nigeria.

| S/No | Sweet potato | Weight of vines per plot (kg) | Longest roots (cm) | Width of longest roots (cm) | Ground cover (%) | Harvest index | Yield of commercial storage roots | Yield of non commercial storage roots | Total yield of storage roots | Fodder yield (top growth) |

| 1 | PGA 14008-9 | 1.5g | 19.0d | 12.0h | 43k | 1.7h | 0.66l | 8.00e | 8.6g | 49.99h |

| 2 | OBARE | 0.5hi | 14.0f | 11.0hi | 60i | 0.8i | 0.66l | 6.66f | 7.3g | 16.66o |

| 3 | KWARA | 0.8h | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 26.66l |

| 4 | NAN | 0.7h | - | - | - | - | 0.66l | 2.00i | 2.6j | 23.33m |

| 5 | CRI-APOMUDEN | 0.3j | 21.0d | 10.0i | 65h | 7.6d | 3.0i | 4.66g | 7.6g | 9.99q |

| 6 | PG17362-NI | 0.3j | 21.0d | 10.0i | 75f | 5.0e | 1.33k | 3.66h | 4.9h | 9.99q |

| 7 | 87/OP/195 | 1.2i | 30.5a | 30.2b | 45k | 12.0b | 38.33a | 10.66d | 48.9a | 39.99l |

| 8 | PGN 16021-39 | 0.4j | 28.1b | 13.0h | 45k | 3.2g | - | 4.33 | 4.3h | 13.33p |

| 9 | CEMSA 74-228 | 0.5hi | 27.1b | 16.0g | 50j | 9.2c | - | 13.66c | 13.6e | 16.66o |

| 10 | TIS 87/0087 (CHECK) | 0.7h | 20.0d | 20.0e | 90c | 5.0e | 1.6k | 10.00d | 11.6f | 9.99q |

| 11 | PGA 14442-1 | 0.5hi | 28.0b | 26.0c | 95b | 25.0a | 23.33b | 18.33a | 41.6b | 16.66o |

| 12 | BUTTER MILK | 2.5f | 24.0c | 23.1d | 90c | 3.8e | 18.66c | 12.33c | 30.9c | 83.33f |

| 13 | PGA 14011-43 | 0.6h | 25.5c | 31.0a | 95b | 5.7e | 15.66d | 16.33b | 31.9c | 22.33m |

| 14 | PGA 14398-4 | 1.0g | 15.0e | 10.0i | 65h | 1.1h | - | 3.66h | 3.6i | 33.33k |

| 15 | CRI-DA DANYUIE | 1.2g | - | - | 50j | 2.14g | 7.0g | 1.66j | 8.6g | 39.99i |

| 16 | LOCAL BEST | 1.2g | 20.0d | 26.0c | 85d | 4.6f | 11.66e | 7.00f | 18.6d | 39.99i |

| 17 | PGA 14372-3 | 1.1g | 25.0c | 30.0b | 83e | 2.3g | 6.0g | 13.33c | 18.3d | 36.66j |

| 18 | CRI-OKUMKOM | 0.6h | 16.0e | 12.0h | 70g | 4.5f | 5.66h | 3.33h | 8.9g | 19.99n |

| 19 | PO3/35 | 7.8a | - | - | 80e | 0.02j | - | 0.66j | 0.6k | 259.99a |

| 20 | PGA 14351-4 | 1.4g | 5.0i | 5.0k | 75f | 0.85i | 2.0ij | 2.00i | 4.00h | 46.66h |

| 21 | UMUSPO/3 (CHECK) | 3.0e | 14f | 9.0j | 85d | 1.73h | 8.66f | 8.66e | 17.3d | 99.99e |

| 22 | TU-PURPLE | 6.2b | 12g | 16.0g | 80e | 1.1h | - | 2.00i | 2.00j | 206.66b |

| 23 | PG 17265-NI | 2.4f | 11g | 22.0d | 100a | 0.09h | - | 5.00g | 5.00h | 79.99g |

| 24 | NWOYORIMA | 5.6c | 20d | 18.0f | 100a | 0.71i | 6.66g | 6.66f | 13.3e | 186.66c |

| 25 | PO3/116 | 4.1d | 8h | 5.0k | 90c | 0.48j | - | 3.66h | 3.6i | 153.33d |

1 = Incidence; S = Severity; SPVD = Sweetpotato Virus Disease

Table 1(b): Number of established plants, growth vigour, number harvested per plot, number of commercial and non-commercial storage roots and weights of commercial and non-commercial storage roots of sweet potato genotypes in Uyo, Southeastern Nigeria.

Table 1(b): Number of established plants, growth vigour, number harvested per plot, number of commercial and non-commercial storage roots and weights of commercial and non-commercial storage roots of sweet potato genotypes in Uyo, Southeastern Nigeria.

17362-NI, nine (9) were creamy, namely PGA 14008-9, Obare, TIS 87/0087 (check), PGA 14398-4, Cri-Dadanyuie, local best, PGA 14372-3, P03/35 and PG 17265-NI, while seven were orange: Cri-Apomuden, 87/OP/195, Cemsa 74-228, Cri-Okumkom, P03/116, PGA 14351-4, UMUSPO/3 (check). Also, three genotypes were yellow (PGN 16021-39, PGA 14442-1 and Butter milk), while one was pale orange, namely Nwoyorima. PGA 14011-43 was pink while Tu-purple was dark purple (Table 2).

Similarly, storage root size and shape of the sweet potato genotypes varied from poor (7), fair (5), fairly good (4), good (3), very good (2) to excellent (1). Root form followed the same pattern. Six sweet potato genotypes produced poor storage root size namely Obare, PGN 16021-39, Cri-Dadanyuie, P03/35, PGA 14351-4 and Nwoyorima, nine were fair (PGA 14008-9, Cri-Apomuden, Cemsa 74-228, TIS 87/0087, PGA 14398-4, Local best, Cri-Okumkom, Tu-Purple, PO3/116, three (3) were good (PGA 14372-3, PG 17362-NI and PG 17265-NI), two (2) were very good (PGA 14011-43 and UMUSPO/13), while three were excellent 87/OP/195, PGA 14442-1 and Butter milk. Similarly, 5 sweet potato genotypes produced poor root form, namely Obare, PG 15021-39, Cri-Dadanyuie, PO3/35, and Nwoyorima while eleven (11) were fair, namely PGA 14008-9, Cri-Apomuden, PG 17362-NI-, Cemsa 74-228, TIS 87/0087 (check), PGA 14398-4, local best, Cri-Okumkom, PGA 14351-4, Tu-purple, PG 17265-NI and P03/116, one was very good, namely PGA 14011-43 and two good, namely PGA 14372-3 and UMUSPO/3 (check). Three sweet potato genotypes produced excellent root form, namely 87/OP/195, PGA 14442-1 and Butter milk. (Table 2)

Number of storage roots with cracks per plot varied significantly (P<0.05). Eight (8) sweet potato genotypes were free of root cracks and rated (0) accordingly, namely Obare, PGA 14398-4, Cri-Dadanyuie, PGA 14372-3, Tu-purple, PG 17265-NI, Nwoyorima and P03/116, while the highest number of cracked storage roots were observed in Cri-Apomuden (33) and 87/OP/195 (25). Similarly, ten sweet potao genotypes recorded no holes in their storage roots, namely, Obare, PG17362-NI, 87/OP/495, Cemsa 74-228, Butter milk, Cri-Dadanyuie, Cri-Okumkom, P03/35, PG17265-NI and P03/116, while the highest number of holes came from UMUSPO/3 (10), followed by three genotypes, each with six (6) holes namely Cri-Apomuden, PGA 14011-43 and PGA 14351-4. (Table 2). Generally, the response of the sweet potato genotypes to biotic reactions was low. Four sweet potato recorded no leaf spot at 4WAP, namely PGN 16021-39, Cemsa 74-228, PGA 14442-1 and PGA 14398-4 and accordingly rated 0 for severity of the diseases at 4 WAP although 3 of the genotypes were affected at 12WAP. Similarly, three sweet potato genotypes were not reactive to sweet potato virus disease (SPVD), namely TIS 87/0087 (check), PG 14398-4, and UMUSPO/3 (check) at 4 WAP although some were later infected at 12WAP, except UMUSPO/3. Sweet potato genotypes with highest incidence to the disease were Obare (5) PGA14008-9 and PG17362-NI (4) and PGN 16021-39 (5), although the severity of the disease reduced with time and age such that at 12 WAP the effect of the disease was moderate on most of the genotypes while three genotypes showed no reaction, namely PGN 16021-39, PGA 14011-43 and UMUSPO/3 (check). Generally, the severity of Alternalia was low for most of the genotypes. However, seven (7) sweet potato genotypes showed no reaction to Alternalia, namely PGA 14008-9, Obare, PGN 16021-39, TIS 87/0087 (check), PGA 14398-4, UMUSPO/3 (check) and Tu-purple (Table 2).

Table 2 shows the starch content (%) of the different sweet potato genotypes with the highest given by Cri-Okumkom (30.04), followed by PG 17265-NI (28.83%), PGA 14442-1 (27.85%) and Cemsa 74-228 (27.56%), while the lowest was produced by Obare (10.5%) and

| S/No | Sweet potato Varieties | Skin colour | Flesh colour | Root size | Root form (cm) | Cracks per plot | Leaf spots 4WAP | Leaf spots 12WAP | SPDV 4WAP | SPDV 12WAP | Alternaria 4WAP | ||||||

| I | S | I | S | I | S | I | S | I | S | ||||||||

| 1 | PGA 14008-9 | Pink | (6) | Cream (3) | 5 (Fair) | 5 (Fair) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | OBARE | Pick | (6) | Cream (3) | 7 (Poor) | 7 (Poor) | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | KWARA | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 4 | NAN | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 5 | CRI-APOMUDEN | Pink | (6) | Orange (6) | 5 (Fair) | 5 (Fair) | 33 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 6 | PG17362-NI | Pink | (6) | White (1) | 3 (Good) | 5 (Fair) | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 7 | 87/OP/195 | Pink | (6) | Orange (6) | 1 (Excellent) | 1 (Excellent) | 25 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 8 | PGN 16021-39 | Yellow | (3) | Yellow (4) | 7 (Poor) | 7 (Poor) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | CEMSA 74-228 | Pink | (6) | Orange (6) | 5 (Fair) | 5 (Fair) | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 10 | TIS 87/0087 (CHECK) | Pink | (6) | Cream (2) | 5 (Fair) | 5 (Fair) | 13 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | PGA 14442-1 | Pink | (6) | Yellow (6) | 1 (Excellent) | 1 (Excellent) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 12 | BUTTER MILK | Yellow | (3) | Yellow (6) | 1 (Excellent) | 1 (Excellent) | 13 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 13 | PGA 14011-43 | Orange | (4) | Pink (7) | 2 (V. Good) | 2 (V. Good) | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 14 | PGA 14398-4 | Pink | (6) | Cream (2) | 5 (Fair) | 5 (Fair) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 15 | CRI-DADANYUIE | Pink | (6) | Cream (2) | 7 (Poor) | 7 (Poor) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 16 | LOCAL BEST | Yellow | (3) | Cream (2) | 5 (Fair) | 5 (Fair) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 17 | PGA 14372-3 | Purple | (8) | Cream (2) | 3 (Good) | 3 (Good) | 0 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 18 | CRI-OKUMKOM | Cream | (2) | Orange (6) | 5 (Fair) | 5 (Fair) | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 19 | PO3/35 | Pink | (6) | Cream (2) | 7 (Poor) | 7 (Poor) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 20 | PGA 14351-4 | Orange | (4) | Orange (6) | 7 (Poor) | 5 (Fair) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 21 | UMUSPO/3 (CHECK) | Pink | (6) | Orange (6) | 2 (V. Good) | 3 (Good) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 22 | TU-PURPLE | Pink | (6) | Dark purple (9) | 5 (Fair) | 5 (Fair) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 23 | PG 17265-NI | Pink | (6) | Cream (2) | 3 (Good) | 5 (Fair) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 24 | NWOYORIMA | Yellow | (3) | Pale orange (6) | 7 (Poor) | 7 (Poor) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 25 | PO3/116 | Purple Red | (8) | Orange (8) | 5 (Fair) | 5 (Fair) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

1 = Incidence; S = Severity; SPVD = Sweetpotato Virus Disease

*The materials had been harvested and kept for a long time before being sent to me, such that some had died resulting in the low number of establishment.

Table 2(a): Skin and flesh colours, root size and form number of cracks and holes, leaf spot, SPVD and alternalia, moisture and starch contents of sweet potato genotypes in Uyo, southern Nigeria.

*The materials had been harvested and kept for a long time before being sent to me, such that some had died resulting in the low number of establishment.

Table 2(a): Skin and flesh colours, root size and form number of cracks and holes, leaf spot, SPVD and alternalia, moisture and starch contents of sweet potato genotypes in Uyo, southern Nigeria.

Table 2: Continued

| S/No | Sweet potato Varieties | No. of storage roots with holes | Moisture content | Starch content (%) |

| 1 | PGA 14008-9 | 2 | 46.92c | 22.26d |

| 2 | OBARE | 0 | 19.11k | 10.51g |

| 3 | KWARA | - | - | - |

| 4 | NAN | - | - | - |

| 5 | CRI-APOMUDEN | 6 | 52.66a | 24.36c |

| 6 | PG17362-NI | 0 | 36.48f | 18.92e |

| 7 | 87/OP/195 | 0 | 39.84e | 26.91bc |

| 8 | PGN 16021-39 | 1 | 24.36i | 18.89e |

| 9 | CEMSA 74-228 | 0 | 50.12b | 27.56b |

| 10 | TIS 87/0087 (CHECK) | 3 | 32.88g | 18.68e |

| 11 | PGA 14442-1 | 2 | 50.64b | 27.85b |

| 12 | BUTTER MILK | 0 | 34.70f | 19.08e |

| 13 | PGA 14011-43 | 6 | 40.94e | 22.52d |

| 14 | PGA 14398-4 | 2 | 21.33j | 11.73g |

| 15 | CRI-DADANYUIE | 0 | - | - |

| 16 | LOCAL BEST | 1 | 50.64b | 22.11d |

| 17 | PGA 14372-3 | 4 | 48.73bc | 26.80bc |

| 18 | CRI-OKUMKOM | 0 | 54.62a | 30.04a |

| 19 | PO3/35 | 0 | 41.76d | 22.96d |

| 20 | PGA 14351-4 | 6 | 42.91d | 23.58d |

| 21 | UMUSPO/3 (CHECK) | 10 | 46.43c | 25.28c |

| 22 | TU-PURPLE | 4 | 26.46h | 14.56f |

| 23 | PG 17265-NI | 0 | 52.41a | 28.83b |

| 24 | NWOYORIMA | 3 | 44.29cd | 24.36c |

| 25 | PO3/116 | 0 | 45.47c | 25.05c |

*The materials had been harvested and kept for a long time before being sent to me, such that some had died resulting in the low number of establishment.

PGA 14398-4 (11.73%). Sweet potato genotypes with high starch content also had high moisture content (Table 2).

Discussion

Variability in qualitative and quantitative characters, biotic reactions and starch contents was observed among the 25 sweet potato genotypes involved in this study. This result agrees with the findings in preliminary evaluation of 17 CIP sweet potato varieties at Umudike, Abia State, Nigeria by Nwankwo et al. (2021). According to Nwankwo and Bassey (2021) variability among sweet potato genotypes is a pre-requisite for genetic improvement and selection using appropriate methods. In this study sweet potato genotypes 87/OP/195 was identified with ten (10) superior characters, namely number of harvested plants per plot, number of commercial storage roots per plot, number of non-commercial storage roots per plot, root size and root form, longest storage roots, absence of holes in storage roots, weight of commercial storage roots (kg) per plot and storage root yield (tha-1), followed by PGA 14442-1 in seven desirable characters, namely: resistance to leafspot, number of non-commercial storage roots, root size and root form, width of longest storage roots, harvest index, starch content and storage root yield (tha-1), both of which were greater than the values obtained from two national checks, TIS87/0087 and UMUSPO/3. However, the result showed that the two top yielding genotypes required further improvement for resistance against sweet potato diseases. The findings agree with Bassey (2017) that most top yielding sweet potato genotypes are usually susceptible to major pests and diseases of sweet potato and called for continuous breeding against biotic factors.

Variability in skin and flesh colours was due to the presence of pigment, carotene, therefore, the skin and flesh colours of 87/OP/195 were pink and orange, respectively. According to Nwankwo et al. (2012), carotenoids in sweet potato are of great health benefit especially in poorer countries where there is no access to vitamin A supplements by the majority of people. Nowadays, consumers of sweet potato prefer varieties with attractive flesh colours. Takahata et al. (1993) associate sweet potato with anti-oxidant effect, capable of improving the health of children and lactating mothers.

The study identified butter milk with second largest number of commercial storage roots per plot and third in weight of commercial storage roots per plot with yellow skin and flesh, excellent root size and root shape and absence of storage root holes and could be placed or rated third in superiority. Since, all the three candidate genotypes show vulnerability to one or two biotic factors, Ngeve (2001) suggested for proper field management as a short term measure, and continuous breeding and selection for resistance along with root yield as long term measure. A recombination of traits through crossing of the three sweet potato genotypes, 87/OP/195, PGA 14442-1 and Butter milk could result in superior genotypes for the environment. From the result, no one individual is totally superior in all the characters and genes could be explored for improvement even in other sweet potato genotypes. Also, P03/35, Tu-purple and Nwoyorima could be further developed and cultivated for fodder, since they are highly vegetative with little or no storage root yields.

Conclusion

Seven (7) sweet potato genotypes, namely 87/OP/195, PGA 14442-1, PGA 14011-43, Butter milk, Uyo local best, PGA 14372-3 and UMUSPO/3 produced storage root yields of 48.999 tha-1, 41.666 tha-1, 31.999 tha-1, 30.999 tha-1, 18.666 tha-1, 18.333 tha-1 and 17.332 tha-1, respectively. However, four (4) of the sweet potato genotypes produced storage root yields greater than the two national and local checks, namely 87/OP/195 (48.999 tha-1), PGA 14442-1 (41.666 tha-1), PGA 14011-43 (31.999 tha-1) and Butter milk (30.999 tha-1). The four top yielding varieties recorded different degrees of resistance to biotic factors and were lower in starch content and could be incorporated into breeding programmes to produce superior hybrid varieties with recombinant genes for not only high storage root yields high resistance to biotic stresses and starch content. However, 87/OP/195 and PGA 14442-1 could be recommended for cultivation as a short term measure in Uyo, southeastern Nigeria.

Acknolwedgements

The authors acknowledge the National Root Crops Research Institute, Umudike, Nigeria for the provision of seed vines and take-off grant for this; Akwa Ibom State Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sufficiency, Uyo, Nigeria for provision of equipment and tractor for land preparation and National Cereals Research Institute, Uyo out- station, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria for the provision of land for this research.

The authors acknowledge the National Root Crops Research Institute, Umudike, Nigeria for the provision of seed vines and take-off grant for this; Akwa Ibom State Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sufficiency, Uyo, Nigeria for provision of equipment and tractor for land preparation and National Cereals Research Institute, Uyo out- station, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria for the provision of land for this research.

References

- Alam, S., Narsary, B.D. and Deka, B.C. (1998). Variability, character association and path analysis in sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam]. Journal of the Agricultural Science Society of North East India, 11: 77-81.

- Antiaobong, E. E., Emosairue, S. O., Ekeleme, F., Wokocha, R.C. and Bassey, E. E. (2009). Economic threshold level and cost benefit ratio of Cyclas puncticollis (Boh) on sweet potato in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Proceedings of International Conference on Research and Development, Volume 1, Number II, November 25 – 28, 2008, Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana. pp. 19 – 24.

- Bassey, E. E. (2021). Handbook of Arable Crop Production for the Tropics and Subtropics, Wilonek Publishers, Uyo, Nigeria, 230p.

- Bassey, E.E. (2017). Variability in the yield and character association in Nigerian sweet potato [Ipomoea (L.)] genotypes. World Journal of Agricultural Science, 5(01): 066-074.

- Bouwkamp, J. C. (1985). Production requirements: sweet potato production, In: Bouwkamp, J.C. (ed.) Natural Resources of the tropics, Boca Raton, Florida CRC Press, pp. 9-33.

- CIP (Centre International des Potato) (2020). Sweet potato – Sect. 1.3 – 99. International Potato Centre, Lima, Peru, South America, p.6.

- Ekpeh, I.J. (1994). Physiography, climate and vegetation of Akwa Ibom State, In: Peters, S.W., Iwok, E.R. and Uya, O.E. (ed). Akwa Ibom State, The Land of Promise: A Compendium, Gabumo Publishing Co. Ltd, Lagos, pp. 239-245.

- Gundadhur, S. (2012). Increasing productivity of sweetpotato through clonal selection of ideal genotypes from open pollinated seedling population. International Journal of Farm Sciences, 2(2): 17-27.

- ICAR (Indian Council of Agricultural Research) (2007). Handbook of Agriculture, Directorate of Information and Publication of Agriculture. Indian Council of Agricultural Research, new Delhi, pp. 512-516.

- Nedunchezhiyan, M., Byji, G. and Jata, S.K. (2012). Sweet potato agronomy. Journal of Agricultural University Puerto Rico, 60(2): 163-171.

- Ngeve, J.M. (2001). Field performance and reaction to weevils of improved and local sweet potato genotypes in Cameroon, In: Akoroda, M. O. and Ngeve, J. M. (eds). Root Crops in the 21st century, Proceedings of the 7th Triennial Symposium of the International Society of Tropical Root Crops African Branch, 11-17 October, pp. 290-297.

- Nwankwo, I. I. M., Bassey, E. E., Afuape, S. O., Njoku, J., Korieoda, D. S., Nwaigwe, G. and Echendu, T. N. C. (2012). Morpo-agronomic characterization and evaluation of in-country sweet potato accessions in south eastern Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Science, 4(11): 281-288.

- Nwankwo, I.I.M and Bassey E.E (2021). Evaluation of some advanced breeder lines of sweet potato for root and fodder yields in Umudike Southeastern Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Technology, 18:1-5.

- Nwankwo, I.I.M and Njoku, T.C. (2019). A review of variability in the flesh root colour of sweet potato as evidence of variety differentiation and their uses. Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Conference of Agricultural Society of Nigeria, held at National Cereals Research Institute, Badeggi, Niger State, Nigeria, 21st – 25th October, 2019, pp. 1-5.

- Nwankwo, I.I.M., Akinbo, O.K., Njoku, T.C., Ikoro, A.I. and Bassey, E.E. (2021). Field evaluation of CIP sweet potato varieties for quality seed vine yield and disease resistance in Umudike, Abia State, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Agriculture, Food and Environment, 20(2): 56-60.

- Nwankwo, I.I.M., Bassey, E.E. and Afuape, S.O. (2014). Yield evaluation of open pollinated sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam] genotypes in humid environment of Umudike, Nigeria. Global Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Health Sciences, 3(1): 199-204.

- Ray, R.C. and Ravi, V. (2005). Postharvest spoilage of sweet potato and the control measures. Critical Review of Food Science and Nutrition, 35: 623-644.

- Shumbusha, D., Shimelis, H. and Rukundo, P. (2019). Gene action and heritability of yield components of dual-purpose sweet potato clones. Euphytica, 215:122.

- Srinivas, T. (2009). Economics of sweet potato production and marketing, In: Loebenstein, O. and Thottapilly, g. (eds.). The sweet potato, Spring Science Business Media, BV, 436-447.

- Stathers, T.E., Rees, e., Kabi, S., Mbilinyi, L., Smith, N., Koizya, H., Jeremiah, S., Nyanjio, A. And Jeiffries, D. (2005). Sweet potato infestation by Cylas species in East Africa, I. cultivar differences in field manifestation and the role of plant factors, International Journal of Pest Management, 49: 137-140.

- Takahata, Y., Noda, T. and Nagata, T. (1993). HPLC determination of b-carotene of sweet potato cultivars and its relationship with colour values. Japan Journal of Breeding, 43: 421-427.

- Tortoe, C. (2010). Microbial deterioration of white variety of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) under different storage structures, International Journal of plant Biology, 1(1):10-15.

- Umoh, A. A. (2013). Rainfall and relative humidity occurrence patterns in Uyo Metropolis, Akwa Ibom State, South-South Nigeria. JOSR Journal of Engineering, 3 (08): 27-31.

- Urgessa, T., Umer, D., Sida, A. and Hayilu, A. (2014). On farm demonstration and evaluation of sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.)] varieties. The case of Kellen and West Wollega Zones, West Oromia, Ethiopia. Journal of Education and Practice, 5(27): 111-116.

- Woolfe, J. A. (1992). Sweet potato: An untapped food resource. International Potato Centre (CIP), Peru/Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 16-19.

Citation: Bassey E. E, Nwankwo I. I. M and Harry G. I. (2022). Field Evaluation of 25 Sweet Potato Genotypes for Qualitative and Quantitative characters, Biotic Reactions and starch Contents in UYO, Southeastern Nigeria. Journal of Agriculture and Aquaculture 4(2). DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.6541007

Copyright: © 2022 Bassey E. E. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.