Research Article

Volume 1 Issue 2 - 2019

Perception and Uptake of Police Action Committee on Hiv/Aids (Paca) Services by Police Officers in Osun State

1MPH; Community Health Department, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

2PhD; Community Health Department, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

3MSc (PT), Physiotherapy Department, Bowen University, Iwo, Nigeria

4MPH; Community Health Department, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

2PhD; Community Health Department, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

3MSc (PT), Physiotherapy Department, Bowen University, Iwo, Nigeria

4MPH; Community Health Department, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

*Corresponding Author: Adagbasa Ehimare, MPH; Community Health Department, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Received: November 07, 2019; Published: November 18, 2019

Abstract

Objectives: This study assessed awareness and opinions of police officers on Police Action committee on HIV/AIDS (PACA) services, assessed uptake of services by police officers, identified factors influencing uptake of services by police officers. It also identified factors influencing implementation of PACA services.

Method: This study was a cross sectional descriptive survey that employ both quantitative and qualitative methods. The study was carried out among police officers in Osun state. A two stage sampling technique was used to select 240 respondents from 3 major towns in Osun State. A semi-structured self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data on socio-demographic characteristics, awareness, and opinions of police officers on PACA services and uptake of PACA services. In-depth interview was used to collect information on factors influencing implementation of PACA services. The data were analysed using statistical product for service solutions (IBM version 23). The data were subjected to univariate, bivariate and multivariate analyses. Tests of association were conducted using chi square and logistic regression. The level of significance was determined at p-value less than 0.05.

Results: The results showed that most of the respondents are within age group 30-49years, 62.9% are males. The level of awareness on PACA services is low among the respondents (72.1%) and also majority of the respondents have negative opinions about PACA services. The level of uptake of PACA services is low among the respondents (65.0%). Very few tested positive to HIV. The proportion of respondents (13.6%) who don’t know their HIV status that had high level of uptake was significantly lower compared to proportion of respondents (50.0%) who tested positive. The factors that significantly influence uptake of PACA services among police officers are sex, place of work. The factors that influence implementation of PACA services are poor funding of PACA activities by donor agencies and the government, low awareness, irregular rendering of PACA records to the national coordinators.

Conclusion: There is low awareness of PACA services among police officers. Majority of the police officers have negative opinions on PACA services. Sex and place of work are factors influencing uptake of PACA services. The factors influencing implementation of PACA services include poor funding of PACA activities by donor agencies and the government, low awareness, incomplete/untimely rendering of PACA records to the national coordinators.

Key words: Perception; Police Action Committee Services; HIV/AIDS

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, 36.7 million people are living with HIV infection worldwide. A decrease in the number of new HIV infections by 6% from 2010 to 2015 has been reported (WHO, 2015; UNAIDS, 2016). Sub-Saharan Africa has the most serious HIV infection epidemic in the world as at 2014, 25.6million people were living with HIV infection in the region accounting for 70% of the global total of HIV infections (WHO, 2015). Only 54% of all people living with HIV infection are aware they have the virus in Sub-Saharan Africa (UNAIDS, 2016). Nigeria accounts for 9% of all people living with HIV infection globally (UNAIDS, 2015). Nigeria as a country has the second largest population of people living with HIV infection and 14% of the global deaths from HIV infection related illnesses are in Nigeria (WHO, 2015). In Nigeria as at 2015, 3.5 million people were living with HIV infection with an adult prevalence rate of 3.1%. There was a decline of the number of new HIV infections in Nigeria from 338,423 in 2005 to 176,701 in 2015 (NACA, 2016).

The Integrated Biological and Behavioural Surveillance Survey in 2014 reported that the prevalence rate of HIV infection among the most at risk population in Nigeria was 22.9% among men who have sex with men, 19.4% among brothel based female sex workers, 8.6% among non- brothel based female sex workers, 3.4% among people who inject drugs, 1.6% among transport workers, 2.5% among police force and 1.5% among armed forces. These groups of people make up 1% of the total population in Nigeria yet account for 23% of new HIV infections in Nigeria (IBBSS, 2014). In Nigeria, the HIV/AIDS infection among the armed forces is being controlled by the establishment of the Armed Forces Program on AIDS control (AFPAC) which was established in 1993 with a primary mandate to strengthen HIV prevention and control and also to provide treatment and care for people living with HIV infection (Sylvia et al., 2002).

Worldwide, military and police force are more at risk of acquiring HIV infection compared to the civilian population and they have increased vulnerability to HIV infection compared to the general population, risk factors for HIV infection among the military include high rates of multiple sexual partner, low rates of condom use with commercial sex workers and other casual partners and significant mixing between groups having high and low risk behaviour patterns (Essien, 2006, Temoshok, 1996). In 2003, UNAIDS estimated that military personnel are two to five times more likely to contract a sexually transmitted infection, including HIV than civilian population. The Nigeria Ministry of Defence in partnership with United State Department of Defence, a military to military partnership established in 2005 had a main objective to provide comprehensive HIV services in 46 military hospitals and medical centers across the country (Walter, 2005). As at 2009, 20 Nigeria military treatment facilities have initiated comprehensive HIV/AIDS services through the Presidents Emergency Plan for AIDS relief (NACA, 2010).

The target population include 80,000 active duty military officers, 750,000 dependents of the military officers and 1,370,000 civilians (NACA, 2010). The United State Department of Defence on HIV program in Nigeria under the President Emergency Plan for AIDS relief program for military officers in Nigeria made provisions for antiretroviral drugs, laboratory infrastructure and staffing support, correct and consistent use of condom, HIV testing services and prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (NACA, 2001). These broad based behavioural interventions also focus on dependents and communities around military posts and have been incorporated as part of the services to be provided by the United States Department of Defence on HIV program in Nigeria in partnership with the Nigeria Ministry of Defence (Walter, 2005).

Police Action Committee on HIV/AIDS (PACA) was also established in 2010 to control the spread of HIV infection among police officers, it was established in all police hospitals across the country to provide services such as prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT), HIV voluntary counselling and testing, provision of anti-retroviral drugs and condoms provision and distribution (Nnenna, 2015). IBBSS (2014) reported low uptake of HIV services among police and military officers.

The uniformed services, especially young men and women, are highly vulnerable to HIV/AIDS because of their work environment, mobility, age and other factors that expose them to higher risk of HIV infection than their civilian counterparts (UNAIDS, 2003). Several factors place men and women of the military and police force at increased risk of HIV infection. First, most military personnel are in the age group at greatest risk of HIV infection namely the sexually active 18-40 years age group. Secondly, these predominantly young persons are typically posted to locations away from their homes and families for extended periods of time (Ekong, 2006). Freed from the strictures of their normal social environments many engage in risky sexual behaviours as a means of relieving the tension of loneliness including the use of drugs and unprotected sex with female sex workers (Okulate et al., 2008). Lack of availability of HIV testing services in most police formations makes it difficult for uniform service men to get the needed HIV testing services (Yeager and kingman 2008).

The impact of HIV infection among uniform service personnels was first recognized by the Security Council when it adopted Resolution 1308 in July 2000 expressing concern over the potentially damaging impact of HIV/AIDS on the health of international peacekeeping personnel. This concern was further emphasized through the adoption of the UN Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS (June 2001), in which the international community and UN member states committed themselves to address HIV/AIDS among uniformed services personnel (UNAIDS, 2003).

In 2000, a US Intelligence Council report estimated HIV prevalence of 40% to 60% among the militaries of war-affected Angola and the Democratic republic of Congo (Bazergan, 2003). Kingma, (2005) reported that Nigerian troops returning to their home communities from peacekeeping missions in West Africa had HIV prevalence rate of more than double the national rate, this raises the possibility of HIV spread to civilian population.

In sub-Saharan Africa HIV prevalence rate among uniform service personnel is 20-40% and rates of 50-60% in countries were HIV/AIDS has been present for more than a decade (UNAIDS, 2003). In South Africa the National HIV prevalence rate was 17.3% compared to that of the police which was 25% (Schonteich, 2003).

In 2017 Malawi reported HIV rates of 22.5% among female police officers and 16.4% among male police officers compared to 8.8% in the general population (Christopher, 2017). In Democratic Republic of Congo the HIV prevalence among Uniform service personnel was 40% which is far more higher than the national prevalence rate of 4.9% (Gordon, 2002, DOD, 2003). While in Angola the HIV prevalence rate among uniform personnel was 60% which was higher than the national prevalence rate of 4.9% (Gordon, 2002, DOD, 2003). In Nigeria HIV prevalence rate among uniform service personnel was 5.3% higher than the national prevalence rate of 3.17% (Ademola, 2017, CIA fact book, 2014).

In Nigeria a study done among military personnel reported that 41.1% of military personnel do not use condom during extramarital sexual intercourse (Ajuwon et al., 2004). Another study done among the military in Kaduna reported that only 4.1% of HIV positive pregnant women are assessing PMTCT services in military hospital Kaduna (Cheshi, 2014). A study of Nigerian peacekeepers found that 7% of peacekeepers contracted HIV after one year of duty, this figure rose to 10% after two years and to 15% after three years (Sarin, 2003). The Nigeria police force is among the most vulnerable group of people to HIV infection (Chidi, 2009). A study done by Nwokoji and Ajuwon (2004) among military men in Lagos reported that 40% of the military personnel who have had sex with a commercial sex worker did so without the use of condom.

A study done among military personnel in south-eastern Nigeria recorded that only 41.1% of military personnel have ever been tested for HIV (Azuogu, 2011).

Asiamah (2004) reported that condom use among Police Officers in Ghana was low, only 50% of officers who had casual sex used condoms. A study conducted among police officers in Ethiopia reported that of the 70% of police officers who are aware of HIV testing services only 24% of the police officers have done HIV counseling and testing (Mitike et al., 2005). A study conducted also in Ethiopia reported that of the 86% of police officers who knew that HIV testing services are easily accessible only 26% have actually used them and of the 81% that are aware of the availability of condoms only 45% of them used them consistently (Roba et al., 2011). Another study done in DareSalaam reported that though 26% of police officers have multiple sexual partners 16% never used condoms (Patricia et al., 2013).

According to recent data from federal police hospital in Ethiopia only 25% HIV positive pregnant mothers are assessing PMTCT services, this is low considering the importance of PMTCT to HIV pregnant mothers. In Nigeria a study done among HIV pregnant mothers attending antenatal clinic at military hospital Kaduna reported that only 4.1% are assessing PMTCT services (Cheshi, 2014). According to the IBBSS report of 2014, condom use among girl friends of police officers was 45.4% which was lower than the armed forces which was 64.7%, condom use at last commercial sex was low among police officers 58.9% compared to the armed forces 86%, condom use during last sex with casual partners among police officers was low 56.2%, compared with armed forces 76.3% (IBBSS, 2014).

The police was found to have lower level of uptake of HIV services compared to the military despite the fact that according to the IBBSS report of 2014, the police force had a better awareness level of HIV infection and also a better knowledge of availability and use of condoms compared to the military (IBBSS, 2014). They also had a better knowledge of HIV transmission routes compared to the military and a lower misconception about HIV infection and a higher personal perceived risk of contracting HIV, yet police officers have a higher HIV prevalence rate than other uniform service men in Nigeria (IBBSS, 2014).

The devastating impact of HIV infection among uniform men is increasingly being recognized by the international community (Pearce, 2008), deaths from HIV infection among uniform men has led to shortages of police work force in some African countries (Pharaoh, 2003). Prolonged HIV and AIDS related cases tend to affect the staff in their ability to work, causing low staff turnover, high recruitment and training cost to replace the deceased officers or those affected, expensive medical care and funeral expenses (Kenya Police, 2006). In Malawi police officers operational efficiency was affected by HIV infection among them (Simon et al., 2008).

In South Africa it has been reported that HIV infected police officers are on most occasion absent from work due to HIV related illnesses (Schonteich, 2003). In some African countries HIV infection has weaken their armed forces to the point of collapse, thus weaken their ability to defend their countries against external aggressors (Elbe, 2003). In Kenya, Uganda & Tanzania uniformed services. The number of deaths and sick leave due to prolonged illness as a result of HIV is on the increase (Lencurran, 2002). In some African countries HIV infection has weaken their armed forces to the point of collapse, thus weaken their ability to defend their countries against external aggressors (Elbe, 2003,UNAIDS 2003).

On PMTCT use by pregnant women Cheshi, 2014 conducted a study on assessing the linkage between prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV in Military hospitals, the study reported low Uptake of PMTCT by wives of military officers, the findings was in agreement with studies done by Okonkwo, 2007 among wives of military officers in Awka who reported low uptake of PMTCT services. Roba 2011, reported low uptake of PMTCT by wives of police officers. Azuogu, 2011 conducted a study on VCT among military personnel, study revealed a low uptake of VCT among military officers. This study was in agreement with studies conducted on uptake of VCT among police officers by mitike, 2005, who reported low uptake of VCT. Simon, 2008 conducted a study on antiretroviral therapy among police officers in the Malawi police force, the study revealed high uptake of ART. Previous studies focused on perception and uptake of HIV preventive services among uniform service personnel.

This study will provide information on perception and uptake of PACA services by police officers and factors influencing implementation of PACA services for police officers in Osun State. The findings from this study might assist policy makers, the Nigeria Police Force and stakeholders to design policies and programmes to overcome the challenges faced during implementation of PACA services in the Nigeria Police Force.

Methodology

A cross sectional descriptive study involving both quantitative and qualitative survey techniques. This study was carried out using a selected Police Hospital located in the selected Police Area Commands in Osun State, Nigeria. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics and Research committee of the Nigeria Police force Osun State command. Permission to carry out study was sought from the Assistant Inspector General of Police (AIG) Zone 11 Osun State. Written informed consent was sought and the officers were assured of the confidentiality of the information given.

This study is limited to only Police Officers resident and working in these Area Commands. These officers are within the age of 18 and 50 years. The police that were mentally and physically ill or were transferred during the course of this study were excluded from this study. Simple random sampling technique via balloting to select about a third of divisional police stations in the three Area commands in Osun state police command. Seven divisional police stations was selected from the 22 divisional police stations at Osogbo Area Command, three from the eight divisional police stations at IIe- Ife Area Command and two from the seven divisional police stations at llesa Area Command to make a total of 12 divisional police stations. The police officers from the selected divisional police stations in the Area Commands was selected proportionate to the estimated population of police officers in the divisional police stations. The quantitative data was collected using a semi-structured, self-administered questionnaire.

There are four sections in the questionnaire: Socio-demographic characteristics of police officers. Awareness of police officers on Police Action Committee on HIV/ AIDS (PACA), Opinions of police officers on PACA services, Uptake of PACA services. One-on-one interview was conducted with state coordinator of PACA at Police clinic Osogbo and the national coordinator of PACA in the Nigeria Police Force using key informant interview. This was used to collect information on available PACA services and the factors influencing uptake and implementation of PACA services in the Nigeria police force. Data was collected by the research assistants and reviewed daily by the researcher after data collection. The qualitative data from the key informant interview was recorded using audio tape recorder and notes taken by research assistants. The key informant interview was recorded after seeking the consent of state coordinator of PACA at police hospital Osogbo and the National coordinator of PACA in the Nigeria police force. Data was collected for a period of five weeks. The quantitative data was entered and analysed using Statistical Product for Service Solutions (IBM SPSS 23.0 version).

Results

Socio-demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondent. The mean age was 39.58 (SD= 7.56). Most of the respondents are within age 30-39years, 32.1% 40-49 years and 10% in age group 50-59 years. Sixty three percent are men and 37% were female. Eighty eight percent are married and 10% are single. Forty seven percent had secondary level of education, while 48% had tertiary education as their highest level of education. Forty one percent are Inspectors, 20% are Sergeant and less than 3% are Deputy Superintendent. Majority are Christians while 24% are Muslim. Seventy five percent are Yorubas, Igbos 12%, 5.8% Hausa while others 7.9% are Igala, Tiv, Nupe etc. forty percent have spent 11-15 years, 33% have spent More than 15 years, while 3% have spent 1-5 years.

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondent. The mean age was 39.58 (SD= 7.56). Most of the respondents are within age 30-39years, 32.1% 40-49 years and 10% in age group 50-59 years. Sixty three percent are men and 37% were female. Eighty eight percent are married and 10% are single. Forty seven percent had secondary level of education, while 48% had tertiary education as their highest level of education. Forty one percent are Inspectors, 20% are Sergeant and less than 3% are Deputy Superintendent. Majority are Christians while 24% are Muslim. Seventy five percent are Yorubas, Igbos 12%, 5.8% Hausa while others 7.9% are Igala, Tiv, Nupe etc. forty percent have spent 11-15 years, 33% have spent More than 15 years, while 3% have spent 1-5 years.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Age group N = 240 | ||

| 20-29 | 9 | 3.8 |

| 30-39 | 128 | 53.3 |

| 40-49 | 77 | 32.1 |

| 50-59 | 26 | 10.8 |

| Mean ± SD | 39.58 ± 7.56 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 151 | 62.9 |

| Female | 89 | 37.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 24 | 10.0 |

| Married | 211 | 87.9 |

| Separated | 4 | 1.7 |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Yoruba | 179 | 74.6 |

| Igbo | 28 | 11.7 |

| Hausa | 14 | 5.8 |

| Others (Igala, Tiv and Nupe) | 19 | 7.9 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 183 | 76.3 |

| Islam | 57 | 23.8 |

| Level of education | ||

| Primary | 14 | 5.8 |

| Secondary | 112 | 46.7 |

| Tertiary | 114 | 47.5 |

| Rank of respondents | ||

| Assistant superintendent | 39 | 16.3 |

| Constable | 34 | 14.2 |

| Corporal | 13 | 5.4 |

| Deputy superintendent | 5 | 2.1 |

| Inspector | 99 | 41.3 |

| Sergeant | 50 | 20.8 |

| Years of service in NPF | ||

| 1-5 years | 7 | 2.9 |

| 6-10 years | 58 | 24.2 |

| 11-15 years | 95 | 39.6 |

| More than 15 years | 80 | 33.3 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic Characteristics of Respondents.

Awareness of Police Officers on Police Action Committee on HIV/AIDS (PACA)

Table 2 shows awareness of police officers on Police Action Committee on HIV/AIDs; 93% reported they have heard of PACA. Of this, Sixty percent are aware of HIV counseling and testing services being rendered by PACA, prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) should be render (15%) and condom distribution (13.8%). Twenty percent reported Doctors should be responsible for providing PACA services, Nurses (26%), laboratory scientist (13%), and health technicians (9%).

Table 2 shows awareness of police officers on Police Action Committee on HIV/AIDs; 93% reported they have heard of PACA. Of this, Sixty percent are aware of HIV counseling and testing services being rendered by PACA, prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) should be render (15%) and condom distribution (13.8%). Twenty percent reported Doctors should be responsible for providing PACA services, Nurses (26%), laboratory scientist (13%), and health technicians (9%).

| Awareness | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Ever heard of PACA (N=240) | ||

| Yes | 223 | 92.9 |

| No | 15 | 6.3 |

| Don’t know | 2 | 0.8 |

| Services that should be rendered by PACA (n = 223) | ||

| HIV counselling and testing services | 134 | 60.1 |

| Prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) | 33 | 14.8 |

| Condoms provision and distribution | 13 | 5.8 |

| Collection of anti-retroviral drugs | 3 | 1.3 |

| Don’t know | 40 | 17.9 |

| Personnel that should provide services (n = 223) | ||

| Doctors | 45 | 20.2 |

| Nurses | 58 | 26.0 |

| Laboratory scientist | 28 | 12.6 |

| Health technicians | 19 | 8.5 |

| All of the above | 24 | 10.8 |

| Don’t know | 49 | 22.0 |

Table 2: Awareness of Police Officers on Police Action Committee on HIV/AIDS (PACA).

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) N = 240 |

| Level of awareness | ||

| Low | 173 | 72.1 |

| High | 67 | 27.9 |

Table 2: Awareness of Police Officers on Police Action Committee on HIV/AIDS (PACA).

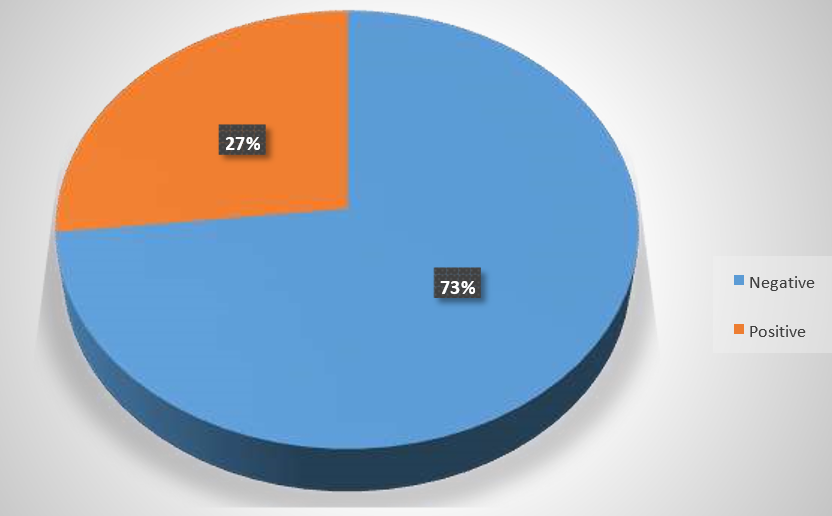

Table 3 shows overall level of awareness of police Officers on PACA services. Seventy two percent had low awareness on PACA services, while 27.9% had high awareness on PACA services. Seventy three percent had negative opinion about the services of PACA while 26.7% had positive opinion on PACA services (figure 1).

Table 4 shows overall level of awareness of police Officers on PACA services. Seventy two percent had low awareness on PACA services, while 27.9% had high awareness on PACA services. Seventy three percent had negative opinion about the services of PACA while 26.7% had positive opinion on PACA services. Figure 1

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Use of PACA services (N=240) | ||

| Yes | 145 | 60.4 |

| No | 95 | 39.6 |

| Services utilized (n= 145) | ||

| HIV counselling and testing services | 79 | 54.5 |

| Prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) |

17 | 11.7 |

| Condoms provision and distribution | 39 | 26.9 |

| Collection of anti-retroviral drugs | 10 | 6.9 |

| Reasons for not accessing PACA HIV services (n = 95) | ||

| Afraid of testing positive to HIV | 42 | 45.3 |

| Afraid of stigmatization | 10 | 10.5 |

| Afraid of disclosure of HIV test results | 9 | 9.5 |

| PACA center too far from place of work/residence | 33 | 34.7 |

Table 4: Uptake of PACA Services.

Table 5 shows the uptake of PACA services by police officers. Sixty percent use PACA services out of which 54.5% reported the use of HIV counseling and testing services, 11.7% Prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) and 26.9% reported on Condoms provision and distribution, 1.2% reported on Collection of anti-retroviral drugs. Forty five percent of the respondents who didn’t access PACA services reported being afraid of testing positive to HIV and PACA centers are too far from place of work/residence (30.3%). Level of uptake of PACA services was low among police officers (65%).

| Level of Uptake | Total χ2 p value | Low | High | n = 145 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Awareness | |||||

| Low | 62 (55.9) | 49 (44.1) | 111 | 16.711 | 0.000** |

| High | 32 (94.1) | 2 (5.9) | 34 | ||

| Opinion | |||||

| Negative | 56 (57.1) | 42 (42.9) | 98 | 7.831 | 0.005** |

| Positive | 38 (80.9) | 9 (19.1) | 47 | ||

Table 5: Association between Awareness and Opinion on PACA services and level of uptake.

Table 5 shows the association between awareness and opinion on uptake of PACA services by police officers. The proportion of respondents (94.1%) with high awareness on PACA services who has low uptake of PACA services was significantly higher than proportion of respondents (55.9%) with low awareness on PACA services with low uptake of PACA services. (χ2 = 16.711, p= 0.000). The proportion of respondents (80.9%) who has positive opinions about PACA services with low uptake on PACA services was significantly higher than proportion of respondents (57.1%) with negative opinions on PACA services with low uptake of PACA services. (χ2 = 16.711, p= 0.000).

Discussion

The study showed that the level of awareness of respondents on PACA services was low. The findings was in disagreement with studies done by Mitike et al, 2005 who reported that though awareness level was high, uptake of HIV preventive services was low. Similarly, most of the police officers are not aware that PACA carry out HIV counseling and testing, but few of them are aware that it is done occasionally. This finding is in line with studies done by Roba et al (2011) who reported that majority of police officers are aware that HCT services are available but very few uses the services (Roba et al., 2011). It is also in keeping with IBBSS report done in Nigeria in 2014, that majority of police officers are aware of HCT services but few uses the services.

The study revealed that more than half of the respondents agreed that PACA services are available. This was in agreement with studies done by Nnenna, 2015 who reported that police officers are aware of PACA services. Majority of the respondents agreed that PMTCT services prevents transmission of HIV from mother to child. This was in line with study done by Roba, 2011, who reported that though police officers are aware of PMTCT services only few are assessing it. The study also showed that majority of the respondents have negative opinions about PACA services. This was in agreement with study conducted among polices officers in Addis Ababa Ethiopia by Feredes, 2005 who reported that police officers have negative opinion about HCT services.

The study revealed that majority of the respondents use PACA services. This was in agreement with studies done by Roba et al, 2012 who reported that most police officers uses HCT, but in disagreement with Mitike, 2005 who reported low use of HCT services by police officers. HIV counselling and testing was mostly utilized by the respondents. This was in agreement with reports of Roba et al, 2012 who reported high use of HIV counselling services by police officers. The major reason given by the respondents for not accessing PACA services is fear to be tested positive to HIV. This was in agreement with reports of UNAIDS, 2003 that the police officers were afraid of doing HIV test. Half of the respondents procure condoms from PACA centres. The level of uptake of PACA services by police officers is generally low this was in keeping with Mitike et al., 2005 who reported low uptake of HIV preventive services by police officers.

The study identified age, sex, educational level, marital status, place of residence, awareness on PACA services and opinion on PACA services as the factors influencing uptake of PACA services. This was in agreement with study done by Fylkensnes, 2004 who reported that age and educational level of uniform service personnel influences their uptake of HIV preventive services, it is also in agreement with studies done by Wring, 2008 who reported that place of residence influences uptake of HIV preventive services.

The study revealed that sex was one of the factors which significantly influence uptake of PACA services by police officers. This was in agreement with a study conducted by IBBSS, 2014 were it was reported that sex of police officers influences uptake of HIV preventive services. Also, place of residence was a factor which significantly influence uptake of PACA services by police officers. This was supported by findings of a study on barriers to HCT service utilization among mobile police force in Zambia by Mulenga, 2010. It was observed that distance of HCT centres from place of residence of police officers determined their uptake of HCT. Age was another factor that influenced the level of uptake of PACA services. This was supported by findings of a study by Fylkensnes, 2004 who reported that age is a factor influencing uptake of HIV preventive services.

The other factors that influence uptake of PACA services include awareness of PACA services and opinion of police officers on PACA services. The study also further revealed that awareness of PACA services by police officers was significantly associated with uptake of PACA services. This was in agreement with report of awareness as a significant factor associated with uptake of PACA services (Lothe, 2007). The study also showed that opinion of police officers on PACA services was also significantly associated with uptake of PACA services. This was supported with a study conducted by Ferede, 2005 who reported that police officers have negative opinion about HIV preventive services.

Conclusion

The study concluded that most of the police officers are not aware of police action committee on HIV/AIDS services. Majority of the police officers have negative opinion about PACA services. The level of uptake of PACA services was low. Approximately seven percent of the police who were tested for HIV were positive. There is a significant association between HIV status and level of uptake. The factors influencing uptake of PACA services are sex and place of residence, level of awareness and opinions of police officers to PACA services. The factors influencing implementation of PACA services includes: poor funding of PACA activities by donor agencies and the government, low awareness of police officers on PACA services, irregular rendering of PACA records to the national coordinators

References

- Ademola, A., Gabriel, M., Hamza, A. and Remi O., (2017). Achievements and Implications of HIV prevention programme among Uniform service personnel, a systemic evaluation of HAF ll project in Kogi State, Nigeria, 2017 pp 613-619.

- Asiamah,G., (2004). Impact of condom wallet on sexual behavior of police officers in Ghana, In: Abstract book of the AXVth international conference on AIDS.

- Ajuwon, A. J. and Nwokoji, U. A. (2004). Knowledge of AIDS and HIV risk-related sexual behavior among Nigerian Naval personnel. BMC Public Health.

- Awoyinfa, F., Egboh, M., and Tugbobo, B., (2004). HIV/AIDS Programs with Uniformed Services: Best Practices from Nigeria. Pathfinder International 25.

- Azuonwu, O., Erhabor, O., & Obire, O. (2011). HIV among military personnel in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Journal of Community Health 2011 May 17.

- Azuogu, B. N. (2011). HIV Voluntary counseling and testing practices among military personnel and civilian residents in a military cantonement in Southeastern Nigeria, 107p.

- Bazergan, R. (2003). Interaction and intercourse. HIV/AIDS and peace keepers, conflict security and development. 3:1

- Bazergan, R and Bayre, G, (2007). HIV and AIDS in Uniformed Services Jan 2007

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, International News, Canada CDC/Hepatitis/STD/TB Prevention

- Cheshi, F. L. (2014). Assessing the linkage between prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV and Adult ART services in two Nigerian military Health facilities in Kaduna, 44p.

- Chidi N. (2009). Police as a high risk group for HIV infection. Vanguard (Lagos) 10th April.

- Christopher .J. (2017). HIV prevalence still high among police officers. The Nation 12th October. 2017.

- Department of Defence HIV/AIDS Prevention Program (DHAPP). 2007 Annual Report for Nigeria.

- Duncan, O. (2016). Effectiveness of HIV and AIDS intervention in Kenya police service, 85p. 23

- Ekong, E. (2006). HIV/AIDS and the Military. In: Adeyi Olusoji, Kanki Phyllis, Odutolu Oluwole, Idoko John., editors. AIDS in Nigeria. Harvard University Press.

- Elbe, S. (2003). HIV/AIDS and the security sector in the southern African region in boas and Hertzj(eds) New and critical security and regionalism. Beyond the nation state. Ashgate Aldershot, United Kingdom pp93-112.

- Emuren, L. Well, S. Evans A.A, Okulicz J.F, Macallino G. and Brian. K., (2017). Health- related Quality of life among Military HIV patients on anti-retroviral therapy 12(6): 178-953.

- Essien, E. J., Ekong, E., Ogungbade, O. O., Ward, D., Ross, M. W., Meshack, A., and Holmes L., (2007). Influence of educational status and other variables on HIV risk perception among military personnel: A large cohort finding. Mil Med; 72 (11): 1177-81.

- Fact sheet (2008). New research from AIDS. (http://img.thebody.com/conf/aids2008/pdf/fs-newresearch.pdf)

- Federal Ministry of Health, Federal Republic of Nigeria. Federal Ministry of Health (2014). HIV/STI Integrated biological and behavioral surveillance survey (IBBSS). Federal Ministry of Health, Federal Republic of Nigeria.

- Federal Ministry of Health Technical Report (2010). National HIV seroprevalence sentinel study, Department of Public Health, National AIDS/STI Control Program.

- Federal Ministry of Health Abuja (FMOH): 2010. Technical report on the National HIV Seroprevalence sentinel Survey among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinics in Nigeria.

- Ferede, S. (2004). Impact and behavioural assessment of HIV/AIDS in Addis Ababa Police force. Addis Ababa. Ethiopia.

- Fylkesnes, K. (2004). A randomized trial on acceptability of voluntary HIV counseling and testing. Trop Med Int Health.

- Gordon, D., (2002). The Next Wave of HIV/AIDS: Nigeria, Ethiopia, Russia, India and China, National Intelligence Council.

- HIV/AIDS. Adult prevalence rate - The World Factbook (2014) Accessed May11, 2016.

- ILO/AIDS, (2010). International labour organization conference adopts unprecedented new international labour standard on HIV and AIDS.

- Joint United Nations Program on AIDS: AIDS and the military, best practice collection.1998.

- Janz, Nancy k; Marshall H. Becker (1984). “The health Belief model: A Decade later”. Health Education and Behavior.11 (1): 1-47.

- Kenya Police (2006). Kenya Police Department Work Station Policy on HIV/AIDS, Kenya Police, Nairobi.

- Kingma, S. and Yeager, R. (2005). HIV/AIDS in Asia – An expanding menace to health and regional security: Challenges for military action. Civil-Military Alliance to combat HIV and AIDS (CMA) 2005.

- Lencurran and Micheal, .M. (2002). HIV/AIDS and uniformed Services: Stock taking of activities in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda 26.

- Local Government Areas: The official website of the state of Osun. Osun.gov.ng. Retrieved 26August 2017.

- Lothe, E. Gurung .M. (2007) HIV/AIDS knowledge, Altitude and practice Survey:UN uniformed peace keepers in Haiti.

- Mitike, G., Haile, Mariam D., and Tsui A. (2011). Patterns of knowledge and condom use among population groups: Results from the 2005 Ethiopian Behavioral Surveillance Surveys on HIV. Ethio Health Dev. 2011, 25 (1).

- Mitike, G. Tesfaye, M. Ayele, R. Gadisa, T. Enqusillasie, F. Lemma, W. Berhane, F. Yigezu, B. and Woldu A., (2005). HIV/AIDS Behavioral Surveillance Survey (BSS), Round Two. Federal Ministry of Health. Ethiopia, 2005 93-105

- Muganzi, A., Baliemuka. M. Anono. C., (2002). Knowledge and acceptability of HIV voluntary counseling and testing among Ugandan Urban youth 14th International AIDS Conference,

- NACA (2010). National Agency for the Control of AIDS. Public Sector Response –Ministry of Defence.

- NACA (2016) National Agency for the Control of AIDS.

- National population commission. Population.gov.ng. retrieved 2017.

- National Action Committee on AIDS (NACA) (2001). HIV/AIDS Emergency Action Plan (HEAP): A Three year strategy to deal with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria.

- Nnenna I., (2015). How sexual abuse by male police officers fuels HIV among female colleagues, Sahara reporters April 9, 2015.

- Norris, A.E.,Phillips, R.E., Statton, M.A, Pearson, T.A (2005) Condom use by male, enlisted, deployed navy personnel with multiple partners, Military Medicine, 2005, 170:898-904

- Nuwaha, F. Kabatesi, D. Muganwa, M. (2002). Factors influencing acceptability of Voluntary counseling and testing in Bushenyi District of Uganda. East African Medical Journal.79 (12). Pp 626-32

- Nwosu, S., (1999). HIV/AIDS and the military. The Airmen journal of Nigerian Air Force.

- Okulate GT, Jones OB, Olorunda MB. Condom use and other HIV risk issues among Nigeria soldiers: challenges for identifying peer educators. AIDS Care. 2008. 20(8): 911–6.

- Patricia, J. M. and Muhammad, B., (2013). Declining HIV-1 prevalence and incidence among police officers a potential cohort for HIV vaccine trials, In Dares Salaam, 722.

- Pearce, H., (2008). The police and HIV/AIDS in the United Kingdom .Journal of security sector management 6(1): 20.

- Pharaoh, R. and Mass A. J., (2003). HIV/AIDS and Attrition: Assessing the impact on the safety, security and Access to Justice Sector in Malawi and Developing Appropriate Mitigation Strategies. 2003, 10-20.

- Roba, A., Berhan, S. and Gudina E., (2012). Influencing preventive behavior with regard to HIV/AIDS among the police force of Harari Region, Eastern Ethiopia, Health, 2012. 3-8.

- Rosenstock, Irwin M; Strecher, Victor J.; Becker, Marshall H. (1997). “The health belief model”. In Andrew Baum. Cambridge handbook of psychology health and medicine. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University press. Pp.113-117.

- Sarin, R., A., (2003). New Security Threat: HIV/AIDS in the Military, World-Watch.

- Schonteich, M. (2003). A Bleak Outlook, HIV/AIDS and the South African Police. South African Crime Quarterly No.5, Southern African Journal of HIV medicine

- Simon, D. M. (2008). Anti-retroviral therapy in the Malawi police force: Access to therapy and treatment outcomes Malawi med J, 20 (1): 23-27.

- Society for Family Health, (SFH), (2017). Training of peer educators from the police action committee n AIDS, cross river state command. Stein, J., (2007). Gelberg-Anderson Behavioural model.

- Sylva, B., Jerome, M. and Scott M., (2002). Knowledge,Attitudes and Sexual Behavior Among the Nigerian Military Concerning HIV/AIDS and STDs, Armed Forces Programme on AIDS Control, 2002:1-95.

- Sherr, L., Lopman B, Kakowa M. (2007). Voluntary Counseling and testing: Uptake Impact on sexual behaviour and HIV incidence in a rural Zimbabwean cohort. 23; 21(7): 851-60.

- Singh, Z. (2006). HIV prevention in the Armed forces: Perception and Altitudes of Regimental officers. Medical journal Armed forces India volume 62, issue 4 p 335-338

- UNAIDS (1998). UNAIDS Point of view: AIDS and the Military – Fact and Figures. UNAIDS Best Practices Collection.

- UNAIDS, (2002). HIV Voluntary Counseling and testing. A gateway to prevention and care.

- UNAIDS, (2003). A guide to HIV/AIDS/STI programming options for uniformed services.

- Engaging Uniformed Services in the Fight against HIV/AIDS Document 1. UNAIDS, (2008). Report on the global AIDS epidemic.

- UNAIDS, (2011). A review of programmes that address HIV among international peacekeepers and uniformed services 2005–2010.

- UNAIDS. Best Practice Collection. Geneva: UNAIDS; 1998. AIDS and the Military.

- UNAIDS Briefing Note on HIV/AIDS in Uniformed Services in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (Unpublished), 2003.

- UNAIDS, (2015), Global report on AIDS 2015

- United Nations Agency for the Control of AIDS Gap Report (2016) - The Gap Report

- UNAIDS, (2015), Global report on AIDS 2015.

- USAIDS, (2004). The President’s Emergency’s Plan for AIDS Relief.

- USAIDS, (2017). Report on the global AIDS epidemic. USAID, (2017). Report on the global AIDS epidemic.

- US DOD, (2003). Proceedings of the Department of Defence HIV/AIDS Programme Review.

- Walter Reed Program Nigeria (2005).

- World Health Organisation, (2015).

- Wring, A. (2008). Uptake of HIV voluntary counseling and testing services in rural Tanzania: Implications for effective HIV prevention and equitable access to treatment. Trop Med Int Health.

- Yeager R, Hendrix C., and Kingma S., (2000). International military HIV/AIDS policies and programs: strengths and limitations in current practice. Mil Med; 165: 87-92.

Citation: Adagbasa Ehimare., et al. (2019). “Perception and Uptake of Police Action Committee on Hiv/Aids (Paca) Services by Police Officers in Osun State”. Journal of Medicine and Surgical Sciences 1.2.

Copyright: © 2019 Adagbasa Ehimare., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.