Research Article

Volume 2 Issue 1 - 2020

Narrative Medicine Research to Evaluate Positive Coping Factors of People Living with MS

1Fondazione ISTUD, Milano

2I primi passi nel mondo della Sclerosi Multipla, Monza, Italy

3Novartis Farma, Origgio

4Department Medical Science and Public Health, University of Cagliari, Italy

5Centro Sclerosi Multipla S. Andrea, Università Sapienza, Roma

2I primi passi nel mondo della Sclerosi Multipla, Monza, Italy

3Novartis Farma, Origgio

4Department Medical Science and Public Health, University of Cagliari, Italy

5Centro Sclerosi Multipla S. Andrea, Università Sapienza, Roma

*Corresponding Author: Antonietta Cappuccio, Fondazione ISTUD, Via Vittori Pisani 28, Milano 20124 Italy.

Received: January 31, 2020; Published: February 10, 2020

Abstract

Purpose: Maladaptive coping strategies are frequently adopted by people with Multiple Sclerosis. The present narrative medicine project aimed to understand the coping factors allowing to achieve a positive reframing of MS through the use of narrative medicine and a standard questionnaire on coping.

Methods: A dedicated on-line platform was set up, and people with MS could enter and share their experiences. Collected narratives were analyzed according to Launer’s classification, (progressive, stuck and in partial progression). In progressive narratives, individuals usually manage to evolve from situations of high complexity and suffering to ones of positive engagement and coexistence with the pathology. Stuck narratives are characterized by a constant situation of disengagement and narratives in partial progression are those in an intermediate phase as they present both positive and negative elements. Coping strategies were assessed using the Brief-COPE questionnaire and within the narratives.

Results: The analysis of the 123 narratives showed that 58% were progressive, 14% were stuck, and 28% were in partial progression. Positive reframing, acceptance, emotional support and instrumental support were factors significantly differentiating progressive from stuck narratives.

Conclusion: The present is the first project carried out on self-reported experiences of people with MS that attempted to combine a validated tool, the Brief-COPE Questionnaire, with a qualitative analysis of narratives to understand the adopted coping strategies.

Through a narrative approach and its application in daily practice, healthcare professionals can understand patient perception in its whole complexity and be able to handle the frailty of these individuals to transform their vulnerability into strength and positive reframing.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Coping factors, Narrative Medicine, Quality of life

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic demyelinating immune-mediated disease that affects the central nervous system (CNS), causing a broad spectrum of signs and symptoms [1]. MS can affect any area of the CNS and is characterized, from a clinical point of view, by a wide variety of signs and symptoms, such as loss of sensitivity, tingling, paresthesia, decrease in muscle tone, spasticity, difficulty in movement and diplopia [2].

The disease in Italy has a prevalence estimated at 188 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, except for Sardinia (360 cases per 100,000 inhabitants) [3]. It is possible to identify different clinical courses of MS depending on its evolution over time [4].

Artemiadis et al. [5] identified a probable relationship between stress and disease progression. Thus, adaptive coping is beneficial for people with MS, not only for reaching psychosocial adjustment to the disease [6]. The word coping refers to the variety of cognitive and behavioral strategies that individuals use during processes to manage psychological stress or the diagnosis of chronic disease [7]. Coping responses are linked in part to personality and in part to the social environment [8].

Maladaptive coping strategies are frequently adopted by people with MS with repercussions not only on the level of perceived quality of life [9] but also on the course of the disease [10]. Numerous studies have analyzed coping strategies used by people with MS, but there is no consensus on the positive strategies that best allow effective adaptation [11, 12]. Instead, an association has been demonstrated between the coping strategies adopted by the person with MS and those used by their caregivers, highlighting that the presence of physical and emotional support can be useful to constructively and realistically manage the burden of the illness [13, 14]. Particularly in couples, coping is fostered when people have clear and open communication that allows the sincere sharing of their physical and mental difficulties [15].

Narrative medicine research seeks to gain insight into how a person lives with his/her illness, in an attempt to consider the many facets of the pathway of care [16]. Narratives allow professionals to collect information on the needs perceived by patients and physicians when coping with distress caused by clinical problems, which can be in part collected by traditional methods, such as structured questionnaires [17]. Many physicians are experimenting with narrative medicine, witnessing its validity in integrating clinical practice, either in reducing anxiety and insecurities in both patients and professionals or revealing gaps in disease treatment, patient support and care or other factors [18]. From an organizational and economic point of view, narrative medicine can be used as a systemic approach to improve the efficacy and efficiency of healthcare services [19].

The narrative medicine project, named “Storie Luminose” (“Bright Stories”) aimed to identify those elements helping to cope with the disease. By "bright story” we intend the sharing of an illness experience that conveys courage, confidence and peace and the desire to be able to find one's lifestyle in the daily management of the disease to those who already share or are facing a similar situation.

Methods

The project was conducted in Italy and invited people with MS to write about their personal experiences in living with MS from June to October 2014.

Subjects were recruited through a promotional campaign on the website of the Italian Multiple Sclerosis Society (AISM), the patients’ forum "I primi passi nel mondo della Sclerosi Multipla" (“First steps in the MS world”) and through the collaboration of 8 most important Italian neurology centers, by informative posters and brochures placed in the clinic’s waiting rooms.

Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of MS and the willingness to share their experiences in writing. No exclusion criteria were given.

Subjects were invited to access the website www.medicinanarrativa.eu/sclerosimultipla and narrate their own experience of living with MS. In the narrative, an illness plot was given to prompt reflections on the past, the present, and the future of living with MS: it was designed through the application of Natural Semantic Metalanguage approach to reduce the researchers’ influence [20]. The purpose of the illness plot was to understand coping factors and help patients to overcome the writer block [20].

Following the narrative section, the Brief-COPE [21] was included to correlate results with narratives on coping. The Brief-COPE questionnaire developed by Carver [8, 21] comprehends 28 items evaluated on a four-based scale. The COPE inventory was validated into Italian before the present project [22], while the Brief-COPE was validated in 2015 [23].

Narratives, all into Italian, were collected through the Typeform online survey platform (http://www.typeform.com/ [cited 2018 Jul 18]) and at the end of the survey period, raw and anonymous results were downloaded as a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. All data were self-reported and submitted anonymously.

All survey instruments received prior approval by a multidisciplinary Scientific Board composed by experts in Multiple Sclerosis management, experts in Narrative Medicine and patient associations’ managers, which were involved in discussing the results and actively contributed through a qualitative consensus meeting. The project was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants had to agree to the online informed consent before writing their experiences. The Ethical Committee of ATS Sardegna approved the project with the protocol 150/2019/C.E.

Data and text analysis

Narratives were analyzed using an approach integrating qualitative and quantitative research, which consist in the qualitative interpretation of stories, through independent reading and classification by 3 researchers, to reduce bias in the interpretation of texts [24]. Quantitative analysis was carried out using specific software, NVivo [25], which enabled the calculation of word frequencies [26]. Launer’s classification of illness narratives [27] and coping factor inventory by Carver [28] were applied to narrative analysis.

Narratives were analyzed using an approach integrating qualitative and quantitative research, which consist in the qualitative interpretation of stories, through independent reading and classification by 3 researchers, to reduce bias in the interpretation of texts [24]. Quantitative analysis was carried out using specific software, NVivo [25], which enabled the calculation of word frequencies [26]. Launer’s classification of illness narratives [27] and coping factor inventory by Carver [28] were applied to narrative analysis.

According to Launer’s classification [27], narratives can be divided into progressive, stuck and in partial progression. In progressive narratives, patients usually manage to evolve from situations of high complexity and suffering, such as the diagnosis and management of MS, to ones of positive engagement and coexistence with the pathology. Contrarily, stuck narratives are characterized by a constant situation of disengagement in which patients cannot accept their new situation and, persistently, show the same fears and negative thoughts. Finally, narratives in partial evolution are those in an intermediate phase as they present both positive and negative elements.

The Brief COPE questionnaire was analyzed according to instructions [21]: it is composed by 28 question and to each question there are 4 possible answers (1 = I haven't been doing this at all, 2= 2 = I've been doing this a little bit, 3 = I've been doing this a medium amount, 4 = I've been doing this a lot). Scales were computed by summing up the scores in these categories: self-distraction, active coping, denial, substance use, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, behavioral disengagement, venting, positive reframing, planning, humor, acceptance, religion, self-blame.

Socio-demographic variables were analyzed with descriptive statistics (mean and ranges, and classes) and frequencies reported as percentages. Standard frequencies of Brief-COPE analysis were calculated using excel; to assess Brief-COPE questionnaire results within stuck and progressive narratives [27] two-tailed tests were used, and p values ≤0.001 were considered statistically significant. Researchers shared the results with the aforementioned multidisciplinary Scientific Board in a validation workshop.

Results

Sociodemographic aspects

The webpage was accessed by 595 individuals, and 123 narratives were collected. As reported in Table 1, subjects were primarily women (100/123), the mean age was 39, and 47 subjects (38%) had at least one child. Table 1 provides data on the geographic residence, level of education and employment status of subjects. The people who shared their story had been living with MS for a mean of 7.8 years and represented all types of MS.

The webpage was accessed by 595 individuals, and 123 narratives were collected. As reported in Table 1, subjects were primarily women (100/123), the mean age was 39, and 47 subjects (38%) had at least one child. Table 1 provides data on the geographic residence, level of education and employment status of subjects. The people who shared their story had been living with MS for a mean of 7.8 years and represented all types of MS.

TABLE 1 Sociodemographic and disease characteristics

| Gender | |

| Woman | 100 (81%) |

| Man | 23 (19%) |

| Age | 39 (18-70) |

| People having children | 47 (38%) |

| Geographic residence | |

| Northern Italy | 51 (41%) |

| Central Italy | 28 (23%) |

| Southern Italy | 44 (36%) |

| Level of education | |

| Middle school | 56 (46%) |

| High school | 15 (12%) |

| University/postgraduate degree | 52 (42%) |

| Employment status | |

| Student | 7 (6%) |

| Employed | 83 (67%) |

| Unemployed | 21 (17%) |

| Retired | 12 (10%) |

| Years of living with the MS | 7,8 (0-36) |

| Type of MS (self-declared) | |

| Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) | 6 (5%) |

| Relapsing-Remitting MS (RRMS) | 87 (71%) |

| Secondary progressive MS (SPSM) | 8 (6,5%) |

| Primary progressive MS (PPMS) | 9 (7%) |

| Progressive-relapsing MS (PRMS) | 8 (6,5%) |

| I don’t know | 5 (4%) |

| Data are presented as n (%) or mean (range). | |

Table 1: Sociodemographic and disease aspects of subjects with MS (N= 123).

Narratives according to Launer’s classification

The analysis of the 123 narratives showed that the 58% were progressive (72/123), 14% (17/123) were stuck, and 28% (34/123) were in partial progression (Table 2).

The analysis of the 123 narratives showed that the 58% were progressive (72/123), 14% (17/123) were stuck, and 28% (34/123) were in partial progression (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Classification of subjects’ narratives

| Progressive narratives | 58% (n =72) |

| “I find my balance, I discover new habits every day, I cope with my limits”, "Today my path with MS is like a country road: sometimes it's sunny, sometimes it's raining and thundering... but I like thunderstorms! Sometimes there's such a wind... you don't know which way to turn to make sure your hair doesn't go on your eyes! I cut them very short: that's how I always see us. No more problems with the wind!” | |

| Stuck narratives | 14% (n=17) |

| “My relations with my husband and his family are a bit tiring ”, "today my path is more complex than before... personal dissatisfaction, I always feel in difficulty, I don't want to give up, but I'm tired... in more than 4 years ago I became cardiopathic after two heart attacks... I feel a bit like in prison..." | |

| In partial progression | 28% (n=34) |

| “The road of my life is yet to be discovered, and… to be lived”, "a disease, for which there is no cure, today, but tomorrow who knows ... so I must wait to follow the therapies that doctors advise me, live the best and try to get to that day in the best possible conditions" |

Table 2: Classification of the 123 narratives in progressive, stuck and in partial progression according to Launer’s classification [25].

The narratives in details

The narratives begin with the description of the events and symptoms from the moment of the breaking of the body’s health status to the present. Considering that the scientific community widely recognized symptoms of MS, we focused our attention on the journey undertaken by individuals to elaborate their condition with MS by choosing the road as a metaphor for life. After the diagnosis (in the past) the road was described mainly as uphill or difficult in 77% of the narratives (Table 4). However, the terminology radically changes in the present, with more positive adjectives of the “road” metaphor, such as bright or flat (44%), and ups and downs or uphill but improving (52%) in progressive narratives. Likewise, the adjectives and the representations used to describe MS itself change and reflect the acceptance process that took place within each person: from a condemnation of life or an enemy to fight with (75%) to a life partner (51%) and an uncomfortable friend (23%). On the contrary, in stuck narratives, the terminology remained negative from the beginning until the present.

The narratives begin with the description of the events and symptoms from the moment of the breaking of the body’s health status to the present. Considering that the scientific community widely recognized symptoms of MS, we focused our attention on the journey undertaken by individuals to elaborate their condition with MS by choosing the road as a metaphor for life. After the diagnosis (in the past) the road was described mainly as uphill or difficult in 77% of the narratives (Table 4). However, the terminology radically changes in the present, with more positive adjectives of the “road” metaphor, such as bright or flat (44%), and ups and downs or uphill but improving (52%) in progressive narratives. Likewise, the adjectives and the representations used to describe MS itself change and reflect the acceptance process that took place within each person: from a condemnation of life or an enemy to fight with (75%) to a life partner (51%) and an uncomfortable friend (23%). On the contrary, in stuck narratives, the terminology remained negative from the beginning until the present.

Narrative analysis examined the relationships with other people in daily life, including those who usually take part to one’s life (family members, friends, colleagues and neighbors). In particular, the illness plot started with "With other people, I was..." in order to understand the real behaviors adopted towards others, but leaving freedom to narrate both challenging and serene relationships. As shown in Table 4, 36% of subjects with MS described serene and open relationships towards others, which are one of the critical factors for achieving adaptive coping. Thirty-six percent of subjects wrote that relationships with others were the same as before without specifying anything further. Thus, this does not allow us to analyze whether the relationships were serene or not. However, 39% of subjects shared their difficulties, of loneliness and closure towards the outside world, sometimes resulting in feelings of anger. Finally, 13% had to reassure others and find the right words to communicate their situation to their families. In the present time, 82% of subjects who cope with MS experienced relationships characterized by serenity, openness and comfort, while this percentage is 34% in stuck narratives.

Following the narrative analysis, another key-factor contributing to positive adaptation to the illness is represented by subjects’ achievements. In particular, individuals developed an inner strength, as well as self-confidence to face a condition recognized as a significant obstacle. Consequently, this awareness resulted in greater care of oneself and the possibility of leading a normal life with a job and hobbies. Furthermore, subjects recounted about their fortune in being able to build a family and maintain solid friendships, despite an illness often leading to isolation. In general, strength and love are two predominant positive factors present in the majority of narratives that allowed individuals to reach a state of well-being. A last emerging factor is the ability to change one’s point of view and rediscover “the little things in life”, to look at the world with new eyes, capable of being amazed and aware of the beauty, finding new passions and interests.

Since the project involved a patients’ online forum and the blog of the patients association, part of the plot investigated the approach of people with MS to the web. More than a half appreciated the possibility of being part of a web community sharing experiences and having the opportunity to talk with other people with MS. As addressed by some subjects, though, the web is a double-edged sword since it is possible to find conflicting information due to variability of the progression of the disease from one person to another causing excessive fear or excessive confidence.

At the end of the plot, subjects shared their vision of the future: 53% of stuck narratives described the future as difficult, while in progressive ones there were different approaches mirroring different coping strategies.

Table 3 The relationship between the evolution of narratives and what subjects expressed in writing

| In the past | Today (progressive narratives) | Today (Stuck narratives) | |

| The road as a metaphor for life with MS | N=113 | N=69 | N=17 |

| Full coping expressions | 3% | 44% | - |

| “My road is in the place I wanted, with the man I love and I will marry”, "I still don't know what my path is. Surely now I have learned to endure, to accept that not everything always goes according to our plans, and we must never give up, but change objectives, change strategy. I have learned that to settle, sometimes, is not synonymous with failure, but it is equivalent to accepting oneself and one's limits.”, "Completely new and tailored to my needs". | |||

| Intermediate coping expressions | 20% | 52% | 18% |

| “My road is always a bit uphill, but I see it much more outlined than in the past. I don't know what awaits me, I don't know how I'll be, but I know that I'll have the person(s) I love at my side, and that's enough for me.”, "My path had simply changed. It was as if my body had rung the alarm bell and shouted to me: "hey! stop and take care of me!” | |||

| Disengaging coping expressions | 77% | 4% | 82% |

| “My road was like an obstacle course, and I didn’t know the route map”, "...uphill, and it's still uphill. Every day you have to make an effort to do something, you have to find the strength to live life, to continue on the road", "...dark, I saw everything black, my only good fortune was that I had been surrounded by my boyfriend who is now my husband too." | |||

| The MS as addressed by patients | N=120 | N=67 | N=15 |

| A life partner, a new point of view | 17% | 51% | 6% |

| “A life partner. It reminds me that I'm not perfect, but that’s my strength”, "An acquaintance whom I would have frequented and whom I would have hoped would have become a friend of mine. You don't hurt your friends, but to earn a friend, you have to be willing", "a different perspective on the world. A condition of being that has stimulated me to change significantly for the better. On certain days it is also a limit and a nuisance, especially in the aftermath of injections. But there are no lives without difficulties. These are the obstacles that make us try new roads or push us to become strong enough to pass them.” | |||

| An uncomfortable friend | 8% | 23% | 20% |

| “It's something I have to live with, especially with the therapy that unfortunately reminds me every day that I'm sick”, "A companion. Bad, but a companion with whom I will spend the rest of my life. More than illness, I like to see it as an unusual way of life!”, “"everyday life. I would lie if I said that I don't think about it... even because if I don't think about it, my diplopia reminds me of it, my continuous tiredness. Once I wasn't like that, but I also try to remedy this... in short… it's an (uncomfortable) friend with whom I have to live, I have to "only" accept it and understand it.” | |||

| Doom, monster, enemy, limitation, unknown | 75% | 26% | 74% |

| “A big question mark on my future, on the possibility of having children and the life I have always dreamed”, "something unknown, I had seen afflicted elderly people and they were all in a wheelchair, so I thought it only led to that", "a disease that wears my brain and digs my bowels, a malefic snake that injects a bit of poison every day to make you die slowly and be aware that your end has not yet arrived ...". | |||

| Relationships with other people | N=112 | N=61 | N=15 |

| Serenity, talking about the disease, courage | 36% | 82% | 34% |

| “I'm always smiling and positive because MS is not the end of life, life must be lived to the best and as positively as possible”, "especially grateful. Because I knew that even if I had to face this new path alone, their help was already precious and their love was and still is indispensable. I was only sorry about their worry, I did not feel sick more than before, indeed stronger, because finally I knew what I had and I could do to feel better.” | |||

| As before, well with few people | 12% | 11% | 33% |

| “I carefully chose who to talk to”, “I do not socialize with many people, but I look for the ones that make me feel better”, "I try to be more normal than I can, I avoid special questions, I only go out when I feel better." | |||

| Avoiding talking, masking the reality, loneliness | 39% | 7% | 33% |

| “I had to learn how to re-modulate my emotions to avoid victimhood and being heavy”, "very grumpy and I blamed all this, everyone", "Those few who are left... I would like to try to be more understanding. They try to stand by me. It's me who doesn't even trust my shadow anymore..." | |||

| Reassuring others | 13% | - | - |

| "Often I found myself having to hear others, even the neurologist, I had managed to displace her by saying: look, doctor, I'm a little slow to react to the cortisone, but I'm not in a hurry, do not worry, when she wants to return, the sight will return.”, "You have to choose whether to keep the news for yourself or not. Each one chooses according to his own situation: I couldn't have hidden it anyway... so I immediately told the truth to everyone, looking for the right words, reassuring and consoling... in indeed, sometimes we have to comfort others." | |||

| Achievements of patients | N=106 | N=64 | N=19 |

| Strength, caring of myself, little things, serenity, hope | 48% | 90% | 37% |

| “I can say that I was proud of myself for not being knocked down, but having lived my life better than before”, "I gained so much optimism that I didn't have before, so much strength and confidence in myself that I didn't think I had before. I can give much more value to the important things in life, to perceive the beauty and value of life and health.” | |||

| Family and friendships | 16% | 10% | 7% |

| "the true friendships, I have revalued many people both those who love me and those whom I have turned away wrong because they did not deserve it. But I've noticed my mistakes, and I'm trying to make up for them by getting closer to some and further away from others","I am more sociable and less closed "to hedgehog" - I take the moment in every situation" | |||

| Normality, job, hobbies, autonomy | 31% | - | - |

| “New hobbies like cycling all together: me, my boyfriend, my friends, my new bike and the MS”, "My achievements have been all and none. I am and I feel like a normal person. I studied, I travel, I have a husband who loves me, a beautiful job, colleagues who appreciate me for what I am and who in their way have learned to joke even about my MS, a wonderful family... I have everything. I don't have children, but patience. I have beautiful grandchildren who love to play and joke with their aunt.” | |||

| No achievement | 5% | - | 56% |

| The web according to patient experience | N=114 | N=58 | N=14 |

| Community for sharing | 18% | 38% | 29% |

| "Fundamental! He frightened me many times, but I could understand that some symptoms I had were normal, that my moods were common to many of us, he made me company when I had no one to talk to" "The web is fundamental. Without my forum, I would be ... lost maybe not ... but I would be much less strong, also because thanks to it now I know wonderful people who have the same disease and with whom I manage this virtual space, and this is wonderful.” | |||

| Useful | 40% | 38% | 43% |

| “to be heard without being seen? I hardly ever do so. The web serves me only as a study, reading, small distractions”, “always important, gives us lots of information, keeps us up to date.” | |||

| Negative, avoided | 23% | 10% | 14% |

| "I'm not a hypochondriac person who checks every single symptom to know which death I have to die of, also because we'll all end up like that, but for the web, it always arrives earlier than expected.”, "I didn't look at anything at that time. I feared the internet as the bubonic plague ... who knows what I would read!” | |||

| With negative and positive aspects | 19% | 14% | 14% |

| "a double-edged weapon. In the beginning, the web was a great container of answers. A quick and easy way to clear up any doubts. So, I believed, before realizing that multiple sclerosis was a pathology with completely singular and unpredictable consequences. It took me a while to educate myself in searching. One thing is to share experiences, emotions and paths. Another is to look for answers to questions that only neurologists or field experts can give you. The web has been fundamental from the beginning to keep me constantly updated on the search. Finding articles in international scientific journals and forums or blogs encourages me day after day. In short, someone works for me, for us. The least I can do is enjoy every little piece of news and progress.” "In this way, the web also continues to be an exceptional tool for the exchange of knowledge. But to exchange knowledge one must have it; the critical sense must never be lacking". | |||

| Tomorrow | - | N=64 | N=19 |

| Difficult, I can’t see it | - | 2% | 53% |

| "at the moment I can't see tomorrow." | |||

| Colorful, better, with my beloved ones | - | 45% | 6% |

| "Tomorrow I will continue to walk on this unpaved path (luckily) continuing to stumble every now and then, just to figure out where I don't have to go, with my MS bassoon on my shoulders. Every now and then it rains, every now and then there's the sun... then flowers and butterflies come out... that's how life is, despite MS everything goes on, quality depends on us.” | |||

| As today, I live the present | - | 29% | 18% |

| "I don't care, I want to live the present in the best way and help my children to be beautiful people", "Unchanged from time to time it seems to me a question mark, but I want to take care of it and not worry about my future.” | |||

| Unknown | - | 24% | 23% |

| "a great question mark made of fears and uncertainty. The only firm point is and will be me, with my ability to always renew myself and to always look for new solutions to things.”, "Foggy but I know I can do it because I'm not alone." | |||

Table 3: Analysis of the narratives in details from the moment of the breaking of patients’ health status to present. We considered various aspects including the road as a metaphor for life with MS, definition of MS according to patients, relationships with other people and achievements of patients in the past and in the present. We also reported direct quotes from the narratives as examples for each analyzed aspect.

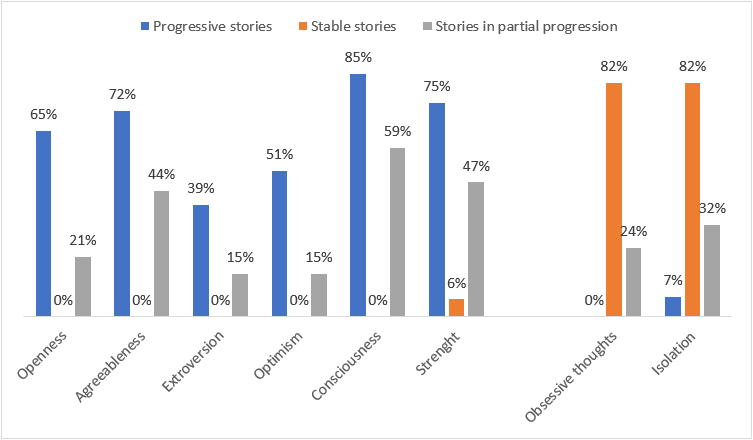

Coping strategies within the narratives Applying the coping factor inventory analysis by Carver to text analysis [29], we found that consciousness, agreeableness and openness were the predominant positive coping factors that encourage engagement with MS (Figure 1). Additionally, we found that strength is also a prevalent positive factor strongly present in the narratives. Conversely, obsessive thoughts and isolation represent negative coping factors that impede adaptive coping with MS (Figure 1). Finally, there was no correlation between different forms of MS, gender and number of years of living with MS and the ability to implement positive coping strategies (Table 3).

Figure 1: Coping factors described within the 123 narratives collected based on Carver classification [33].

TABLE 4 The relationship between the evolution of narratives and the various forms of MS

| Progressive narratives | Stuck narratives | Narrative in partial evolution | |

| Type of MS (self-declared) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) |

| CIS | 67 (4) | 33 (2) | 0 (0) |

| RRMS | 61 (53) | 7 (6) | 32 (28) |

| SPSM | 57 (5) | 43 (3) | 0 (0) |

| PPMS | 44 (4) | 33 (3) | 22 (2) |

| PRMS | 63 (5) | 25 (2) | 12 (1) |

| Don’t know | 20 (1) | 20 (1) | 60 (3) |

| Gender | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) |

| Female | 60 (60) | 13(13) | 27 (27) |

| Male | 52 (12) | 17(4) | 31 (7) |

| Years of living with the MS | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) |

| From 1 to 12 months | 53 (10) | 5 (1) | 42 (8) |

| From 1 to 5 years | 63 (27) | 16 (7) | 21 (9) |

| From 6 to 10 years | 50 (12) | 8 (2) | 42 (10) |

| From 11 to 15 years | 58 (11) | 21 (4) | 21 (4) |

| From 16 to 36 years | 67 (12) | 17 (3) | 17 (3) |

Table 4: The relationship between the evolution of narratives, the various forms of MS, gender and number of years living with MS. The two-tailed test did not show statistically significant differences (p > 0.01).

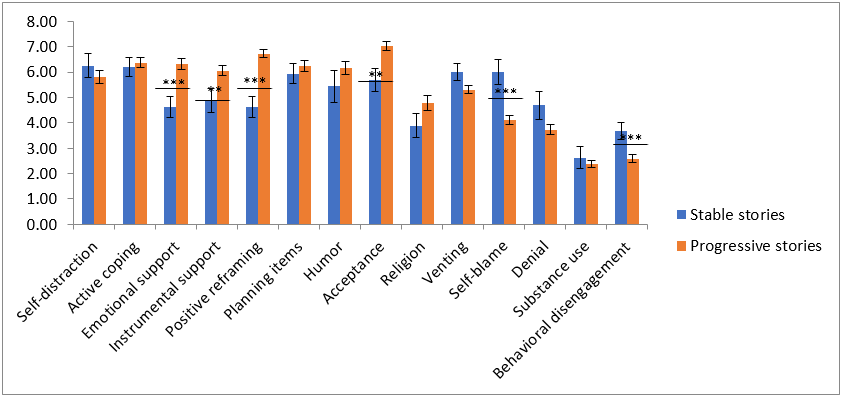

Analysis of the Brief COPE questionnaire Overall, the results of the Brief-COPE [21] are in accordance with what emerged from the analysis of the narratives. As reported in Figure 2, the positive factors that show statistically significant differences among stuck narratives and progressive narratives included the ability to have a positive perspective (positive reframing, p<0.001), the acceptance of one’s condition of living with MS (acceptance, p<0.01), the support of loved ones in emotional and instrumental terms (emotional support, p<0.001; instrumental support, p<0.01). Conversely, the tendency of blaming oneself (self-blaming, p<0.001) and avoiding stressful situations rather than solve them (behavioral disengagement, p<0.001) were prevalent negative factors that characterized stuck narratives. No statistically significant differences were found for self-distraction and active coping, as well as for other factors such as planning, religion and venting. Although generally in accordance with the analysis of the narratives, we found that the Brief Cope failed to give a picture consistent with the reality reported in the narratives in 27% of cases. In particular, 83% of this latter are false negatives: progressive narratives in which Brief-COPE cannot detect an evolution among past and present and therefore a positive acceptance of the MS.

Figure 2: Brief COPE analysis evidences that the positive factors that show statistically significant differences among stuck narratives and progressive ones (N=123) are positive reframing (p<0.001), acceptance (p<0.01), emotional support (p<0.001), and instrumental support (p<0.01). On the contrary, the prevalent negative factors in stuck narratives are self-blaming (p<0.001) and behavioral disengagement, (p<0.001). No statistically significant differences were found for the other factors.

Discussion

The present is the first project carried out on self-reported experiences of people with MS that attempted to combine a validated tool, the Brief-COPE Questionnaire, with narrative medicine to understand coping strategies adopted by people with MS.

Consistent with the expectation [7], both from narratives and the Brief-COPE, adverse experiences were characterized by maladaptive coping strategies such as isolation, obsessive thoughts and behavioral disengagement. From the Brief-COPE questionnaire, self-blaming also emerged as a negative coping factor, however from the narratives the same people were also blaming others, venting and living with a pessimistic mood.

While in previous studies growth [11] and acceptance [29] were considered positive coping strategies able to reduce depressive symptoms, emotional support and positive reframing predominantly emerged from present analysis. Positive reframing, highlighted by the Brief-COPE questionnaire, is better described within narratives: in particular, 90% of progressive narratives recalled this strategy as the consciousness of appreciating little achievements and listening to one’s own body, the awareness of being stronger than before the diagnosis and the capability of not losing hope. This description confirms the results of other studies in which self-esteem is associated with positive coping factors [12]. Indeed, individuals who wrote a progressive narrative were generally proud of themselves for how they cope with MS, also thanks to the help of their loved ones.

Instrumental support, in other words, the capability of asking help and advice from others, emerged from the Brief-COPE as a positive strategy. From the narrative analysis, people with MS found help not only from relatives and healthcare professionals, but also from a web community of people living their same experiences. In particular, Internet had a dual function: sharing experiences and finding a supportive community, and checking symptoms and searching for new treatments, as previously observed by other studies [30]. Although, in the present study, this second approach seems to be disengaging and related more to “stuck narratives”.

However, the present research presents some limitations. A first limitation is given by the fact that the project was titled “Bright Stories”, resulting in a natural selection of people who self-evaluated themselves as being able to share a positive experience, even though 14% decided to participate sharing a negative experience with MS. Even considering this bias, the 123 people who decided to narrate their experiences well represent the Italian MS population [3] with the only difference being a predominantly female cohort. Other limitations of the present research are the restriction of narratives collection to Italian language and through an online platform. Finally, the Brief-COPE was validated into Italian in 2015, after the collection of narratives; however, results can now be considered as valid.

In conclusion, this study highlighted different coping strategies and suggested that narrative medicine can provide more meaning and explanation of subjects’ personal experiences with illness than a questionnaire. This study highlighted coping strategies related to progressive narratives, and these stories can be inspiring for others diagnosed with the same condition [16]. These analyses also pointed out risk factors that all healthcare professionals, from physicians to decision-makers, should be aware of, including the use of the Internet, the importance and potential of networks for people with MS and the importance of improving disease awareness in general to facilitate the relationships with colleagues and friends. Through narrative medicine and its application in daily practice [17], healthcare professionals can understand patients’ perceptions in their complexity and be able to encourage people with MS to transform their vulnerability into strength and positive reframing.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Novartis Farma Italia for its unconditional contribution to this study, to Hospital San Martino of Genoa, San Raffele Hospital in Milan, Santissima Annunziata Hospital in Chieti, Policlinic of Bari, Federico II Hospital in Naples, Vittorio Emanuela Policlinic in Catania, MS Center of the University of Cagliari, the Italian Multiple Scleosis Society (AISM) in the person of Michele Messmer Uccelli and the forum “I primi passi nel mondo della sclerosi multipla” which helped in collecting the narratives, the researchers Riccardo Ruggero and Maria Rosa Adelini for their useful role throughout this project and, above all, all the people with MS who shared their experiences of living with the disease.

The authors wish to thank Novartis Farma Italia for its unconditional contribution to this study, to Hospital San Martino of Genoa, San Raffele Hospital in Milan, Santissima Annunziata Hospital in Chieti, Policlinic of Bari, Federico II Hospital in Naples, Vittorio Emanuela Policlinic in Catania, MS Center of the University of Cagliari, the Italian Multiple Scleosis Society (AISM) in the person of Michele Messmer Uccelli and the forum “I primi passi nel mondo della sclerosi multipla” which helped in collecting the narratives, the researchers Riccardo Ruggero and Maria Rosa Adelini for their useful role throughout this project and, above all, all the people with MS who shared their experiences of living with the disease.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The project was supported by an unconditional grant of Novartis Farma Italy.

The project was supported by an unconditional grant of Novartis Farma Italy.

Conflict of interest: CP has served on scientific advisory boards for Actelion, Biogen, Genzyme, Hofmann La Roche Ltd, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Sanofi, Teva, and has received consulting and/or speaking fees, research support and travel grants from Allergan, Almirall, Biogen, Genzyme, Hofmann-La Roche Ltd, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Sanofi and Teva. EC serves on scientific advisory boards and received honoraria for speaking from Bayer, Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme Roche and Teva. FF is an employee of Novartis Farma. ML is now an employee of Celgene. AC, MGM, LP have no conflict of interests to declare.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in the project involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. The project was approved by the Ethical Committee of ATS Sardegna with the protocol 150/2019/C.E.

Informed consent: Online informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the project.

References

- Cohen JA, Rae-Grant A. Handbook of Multiple Sclerosis. 2nd ed London, UK: Springer Healthcare; 2012.

- Karussis D. (2014 ). The diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and the various related demyelinating syndromes: a critical review. J Autoimmun. Feb-Mar;48-49:134-42.

- Bandiera P. (2018 ). Multiple Sclerosis Barometer. Genoa, Associazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla; [cited 2018 Jul 18].

- Lublin F.D, Reingold SC, Cohen JA et al. (2014). Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis:The 2013 revisions. Neurology 83:278–286.

- Artemiadis A, Anagnostoulis MC, Alexopoulos EC. (2011). Stress as a risk factor for multiple sclerosis onset or relapse: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology. 36: 109– 120.

- Lode K, Larsen JP, Bru E, Klevan G, Myhr KM, Nyland H, (2007). Patient information and coping styles in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 13:792-9.

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. (2004). Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annu Rev Psychol. 55: 745– 774.

- Carver, Charles S.; Connor-Smith, Jennifer (2010). "Personality and Coping". Annual Review of Psychology 61: 679–704.

- Goretti B, Portaccio E, Zipoli V et al (2009). Coping strategies, psychological variables and their relationship with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci 30:15–20.

- AIKENS JE, FISCHER JS, RUDICK R. (1997). A replicated prospective investigation of life stress, coping, and depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. J Behav Med 20: 433–55.

- Grech LB, Kiropoulos LA, Kirby KM, Butler E, Paine M, Hester R. (2018 ). Target Coping Strategies for Interventions Aimed at Maximizing Psychosocial Adjustment in People with Multiple Sclerosis. Int J MS Care. May-Jun;20(3):109-119.

- Bianchi V, De Giglio L, Prosperini L et al. (2014). Mood and coping in clinically isolated syndrome and multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. Jun;129(6):374-81.

- EHRENSPERGER MM, GRETHER A, ROMER G et al. (2008). Neuropsychological dysfunction, depression, physical disability, and coping processes in families with a parent affected by multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 14:1106–12.

- Pozzilli C, Palmisano L, Mainero C, et al. (2004). Relationship between emotional distress in caregivers and health status in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. Aug;10(4):442-6.

- Busch AK, Spirig R, Schnepp W. (2001). Coping with multiple sclerosis in partnerships : A systematic review of the literature. Nervenarzt 2014 May 11.-German Bury M. Illness narratives: fact or fiction? Sociol Health Illness.

- Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B: (1999). Why study narrative? In: Narrative based medicine: dialogue and discourse in clinical practice. (Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B, eds) London: BMJ Books, 3–16.

- Marini MG, (2016). Narrative Medicine: Bridging the Gap between Evidence-Based Care and Medical Humanities. Springer International Publishing,

- DasGupta S, Charon R: (2004). Personal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med 79: 351-356

- Greenhalgh T. (2016). Cultural contexts of health: the use of narrative research in the health sector. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; (Health Evidence Network (HEN) synthesis report 49); [cited 2018 Jul 18].

- Peeters B., Marini M.G. (2018). Narrative Medicine Across Languages and Cultures: Using Minimal English for Increased Comparability of Patients’ Narratives. In: Goddard C. (eds) Minimal English for a Global World. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Carver CS. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 4(1):92-100.

- Muller L, Spitz E. (2003). Multidimensional assessment of coping: validation of the Brief COPE among French population. Encephale. Nov-Dec;29(6):507-18.

- Monzani, D., Steca, P., Greco, A., D’Addario, M., Cappelletti, E., & Pancani, L. (2015). The Situational Version of the Brief COPE: Dimensionality and Relationships with Goal-Related Variables. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 11(2), 295-310.

- Richards L, Richards T. (2013). The Transformation of Qualitative Method: Computational Paradigms and Research Processes. In: Using Computers in Qualitative Research (Fielding NG, Lee RM, eds). London: Sage, 1991; 38-53.

- Bazeley P, Jackson K. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. London: Sage, 68-73.

- Kelle U, Laurie H. (1995). Computer Use in Qualitative Research and Issues of Validity. In: Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis: Theory, Methods and Practice (Kelle U, ed). London: Sage, 19-28.

- Launer J. (2006). New stories for old: narrative-based primary care in Great Britain. Families, Systems and Health. 24(3):336-344.

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. (1989 ). Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. Feb; 56(2):267-83.

- Pakenham KI, Fleming M. (2011). Relations between acceptance of multiple sclerosis and positive and negative adjustments. Psychol Health. 26: 1292– 1309.

- Brigo F, Lochner P, Tezzon F, Nardone R. (2014). Web search behavior for multiple sclerosis: An infodemiological study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. Jul;3(4):440-3.

Citation: Antonietta Cappuccio., et al. (2020). Narrative Medicine Research to Evaluate Positive Coping Factors of People Living with MS. Journal of Medical Research and Case Reports 2(1).

Copyright: © 2020 Antonietta Cappuccio. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.